The strict enforcement of writing styles is something that I think bugs most of us. Every academic profession has their own writing style. Chicago (which is what Historians use), MLA, APA, etc. we’ve all heard of them and we’ve all probably used at least a couple of them before. But they are constraining and obnoxious.

Historically speaking, manuals of style are actual quite young. Only dating back around a century or so at the most, manuals of style weren’t even all that popular outside of their original institution until a few decades ago. Among famous writers and essayists like J.R.R. Tolkien and George Orwell, manuals of style are a foreign concept. So why do we use them today?

The HR mammy longhouse. That’s why.

In part, manuals of style are a necessity as (((stupid people))) are brought in to academic institutions and must have their hand held like the intellectual infants that they are. They simply can’t be trusted to write coherently unless they adhere to a strict set of rules.

The other half is the general desire to fabricate conformity in academia. Telling people how they can write is merely the first step in telling them what they can write.

How I Write

If you all haven’t noticed, my personality is a synthesis of the aristocratic man and the simple man. I oscillate between a state of refined intellect and unrefined banality. This is because I think this is the best way to understand the world and, more importantly, to lead it. The best leaders were always in touch with their people on an intimate, personal, level while simultaneously existing as something else. Something more. This is also how I write (when I am not LARPing for school anyways).

Your writing should simultaneously be intellectually rigorous and palatable to the layperson. One of the most influential works on my writing philosophy is George Orwell’s short essay Politics and the English Language. In it, Orwell notes how language can be used to obfuscate one’s true intentions:

The great enemy of clear language is insincerity. When there is a gap between one's real and one's declared aims, one turns as it were instinctively to long words and exhausted idioms, like a cuttlefish spurting out ink.1

Orwell provides a quite humorous example of what he means by translating Ecclesiastes 9:11:

I am going to translate a passage of good English into modern English of the worst sort. Here is a well-known verse from Ecclesiastes:

I returned and saw under the sun, that the race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, neither yet bread to the wise, nor yet riches to men of understanding, nor yet favour to men of skill; but time and chance happeneth to them all.Here it is in modern English:

Objective considerations of contemporary phenomena compel the conclusion that success or failure in competitive activities exhibits no tendency to be commensurate with innate capacity, but that a considerable element of the unpredictable must invariably be taken into account.2

Simplicity, honesty, and avoidance of verbiage.

I also generally avoid using the third person as much as possible. I am writing the paper, the paper is not arguing anything. The paper is inanimate. More importantly, I am writing to you, the reader. I want to address you as a person and I want you to think of me as a person. When I am drafting these essays in my head (usually in the shower or as I write them), I do so as if you and I were having a conversation on the topic, or if I was addressing a crowd. I think the notion that using the third person somehow strengthens your argument is ridiculous. Not only is it ridiculous, but it is also cheap. I do not need to rely on linguistic tricks to strengthen my arguments. Let the merit of my arguments stand solely on the truth of my premises and the validity of my logic.

Similarly, I rarely allege my arguments as empirical fact. If you’ve read the about section of The Knox Papers, then you know that I consider myself a “Rationalist with Empiricist influences” and, to put this in laymen’s terms, this basically means that I prize reason above all, and while I prefer to have material evidence I don’t need it (more on that in the next section). What this means, in practice, is that I make reasoned extrapolations based on evidence, but I don’t always necessarily have evidence explicitly stating my point. For this reason, you will rarely see me expressly claim a particular truth when discussing history. Most of the time I will simply say “it’s a lot more complicated than what people say” or “it’s impossible to know for sure, but I am led to believe that…” instead of making declarative statements like most historians are wont to do. As such, it it also more fitting to use the first and second person when writing because I am not outlining some objective and universal truth, but instead what I have been led to believe by means of the available evidence and reasoned abstraction. I approach History from a probabilistic and nuanced perspective; I look at the probability of historical narratives being true or not (this is generally known as a post-structuralist perspective).

This is also why, in my previous post Academic Neuroticism, I have outlined my grievances with academic history. On some level, these historians seem to know what they are saying is unlikely to be true, or even just plain false, but instead of being clear about this, they obfuscate their point through clever linguistic constructs and logical fallacies. For a more specific example of what I mean by this, see my previous post titled: Guns, Germs, and Steel (and a LOT of Cope). As I like to say: “Tautologies, circular reasoning, and the genetic fallacy are the historian’s best friends.”

For similar reasons, I like to refrain from providing analysis of my sources until after they have been presented in their entirety. For example, my recent post America's Christian Heritage features extensive passages from colony charters and state constitutions, but each quotation is accompanied only by a brief synopsis of what the quote itself says for simplicity’s sake. The actual analysis of the documents doesn’t come until I have presented all relevant documents, by which point you have probably come to the same conclusions that I outline.

Inevitably, elements of the Chicago Manual of Style (the manual of style used by Historians) have become a part of my own personal style. I don’t really see this as a big deal, because I have not allowed it to constrain my writing (outside of mainstream academic circles anyways) and so I continue to be authentic. Oftentimes, I play into it as part of the whole “aristocratic man” thing so really it works itself out.

Citations and Sources

“Sources And A Quick Note About Citations

I don’t cite sources out of some misguided notion of academic credibility. I cite sources because it fosters a sense of community, it engages others, it connects people. I cited Zero HP, BAP, Bennett, and L0m3z as a small but potentially useful form of subversion. In citing your kin, you recognize them as a source of intellectual authority. When we refuse to reference gay academics, we knock them down a rung. From now on, I recommend citations as a means to expand our community, delegitmize outsiders, and foster a sense of authenticity within our community. I have also intentionally avoided MLA formatting simply because I dislike teachers and rigid rules for writing. You should too.”

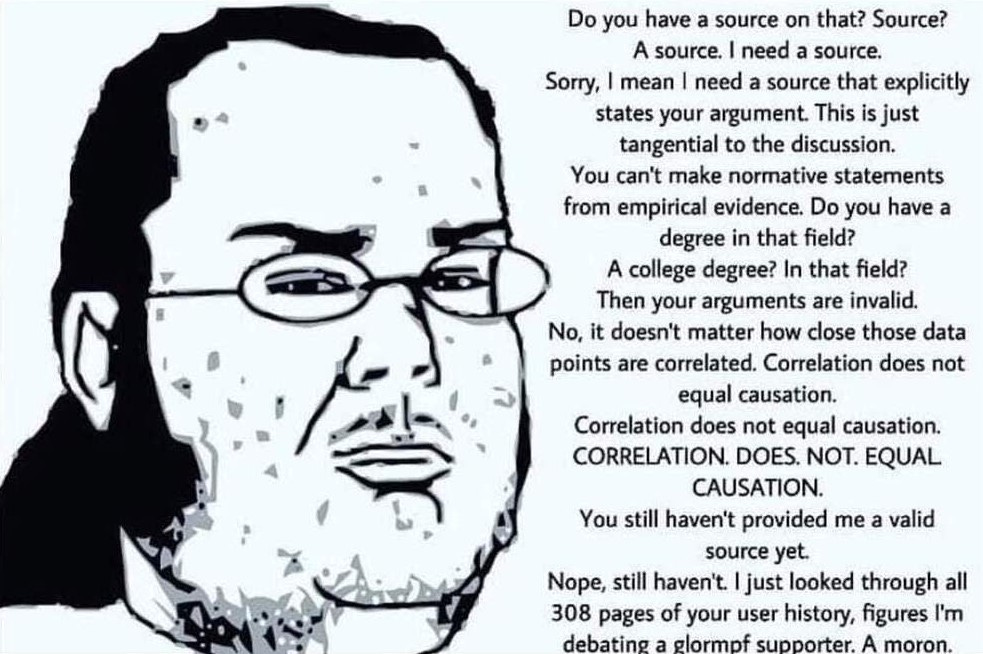

The sentiment expressed in the above quote from Lionel is quite common in our circles. On some level it is a reaction to soy-brained Redditors.

It is inarguable that, on some level, this sentiment that is so often expressed by the Right is reactionary. Frankly, I can’t blame them. The above meme raises a lot of valid complaints and I myself have encountered people like that and I find them extremely annoying. These people generally don’t actually care about reading any sources you may or may not have. They just want to catch you with your pants down and have a trump card because you can’t provide a bibliography for your argument with a stranger on the internet that you started while you were on the toilet.

These people are not intellectually honest. You can always tell because if you tell them to look something up themselves, even if you give very specific keywords to search, they will throw their hands up in the air and proclaim that you clearly just made it up and are backpedaling. The reality is, you don’t keep your chud archives on your phone and you won’t be home from work for another few hours.

So yeah, I get it. These people are annoying. I also agree with Lionel that academics are gay and you shouldn’t cite them if it can be avoided (or you are making fun of them). In fact, I have expressed similar dissatisfaction in a few of my previous posts: Activism In The Modern Age, Academic Neuroticism and A Historian's Grievances. What I don’t agree with, however, is that citing sources is irrelevant or unnecessary. I’ve talked about this some before (again, see the previous posts), but never in as much detail as I plan on doing here.

Let me give you a few general rules that I cite by:

Avoid citing contemporary scholars when possible.

Most scholars are lame. Some aren’t. Dr. Ray Blanchard (best known for coining the term “autogynephilia”) is a contemporary scholar who isn’t lame.

Citing older historians, from the mid 20th century or before, is a nice work around. Just make sure that you are aware of any counterarguments that (lame) contemporary academics like to use. And of course, make sure they are actually correct.

Rely on primary sources. Cite these instead of contemporary scholars (secondary sources). This way you still have something to lob at the soy-brained Redditor, without relying on contemporary scholars.

If you can, always include the source in such a way that your reader can read it just as easily as they read your article. I like to do this by finding the work on archive.org, finding the exact page number, and then including a link to the work and page number in my article. This way your readers can easily read what you’re reading, AND they can use the same source in their own works/arguments.

Don’t cite encyclopedias (tertiary sources) and especially not Wikipedia. These sources are like secondary sources except they have even lower standards for academic integrity.

If you want to include links to encyclopedia entries in your article to contextualize things for your reader (as I did above) then that’s fine, just don’t rely on that in your argument.

Generally adhere to a manual of style for citations. I know I said earlier that I don’t really like manuals of style (still don’t) but following them for citations does generally tend to make things a lot easier and clearer.

Reference other RW writers/thinkers. Like Lionel said, it’s important for us to subvert contemporary academia while simultaneously propping ourselves up as the alternative. I frequently quote other writers on Substack (as I did with Lionel) and point my readers to similar articles written here. You should do the same.

Include a dedicated “further reading” section if you can. If someone has a slightly different take, or covers a tangential topic, or goes into more depth, then let your readers know!

Compile chud archives. Stats, documents, facts, YouTube/Odysee videos, graphics, whatever. Gather them up, and put them in a Google drive or something. It saves a lot of frustration and generally makes things easier.

I kinda more or less am writing a sort of style manual. Is there any advice you want to give me for this endeavor?

The biggest crime of Longhouse Occupied Literary Space is that, not only does it constrain academia, but it also cripples experimentation in the creative sphere; restricting everything to The Formula (smut). It makes everything so, so boring.