The Polk Post

Why Polk is FREAKING Epic

This post has been a long time coming. It was highly requested back when iFunny was still a viable option for textposting, before the automod got so bad that anything with more than 30 words was shadowbanned instantly.1 I posted some content on Polk, namely a comprehensive reading list and sharing some pictures from the Polk Museum that I took when I toured it (I think both have since been lost during the “I hope you have backups…” iFunny bucket hack), but I never got around to posting a proper “Polk Post” until now. Accordingly, this post will cover three primary topics:

The first part will be biographical and historical information;

The second will be my opinions on him and why he is historically and culturally important; and

Finally the last part will be a comprehensive reading guide for both Polk biographies and primary source material (Polk’s diaries, correspondence, etc.) and some of the adjacent topics, like the Mexican-American War and Sarah Polk (his wife).

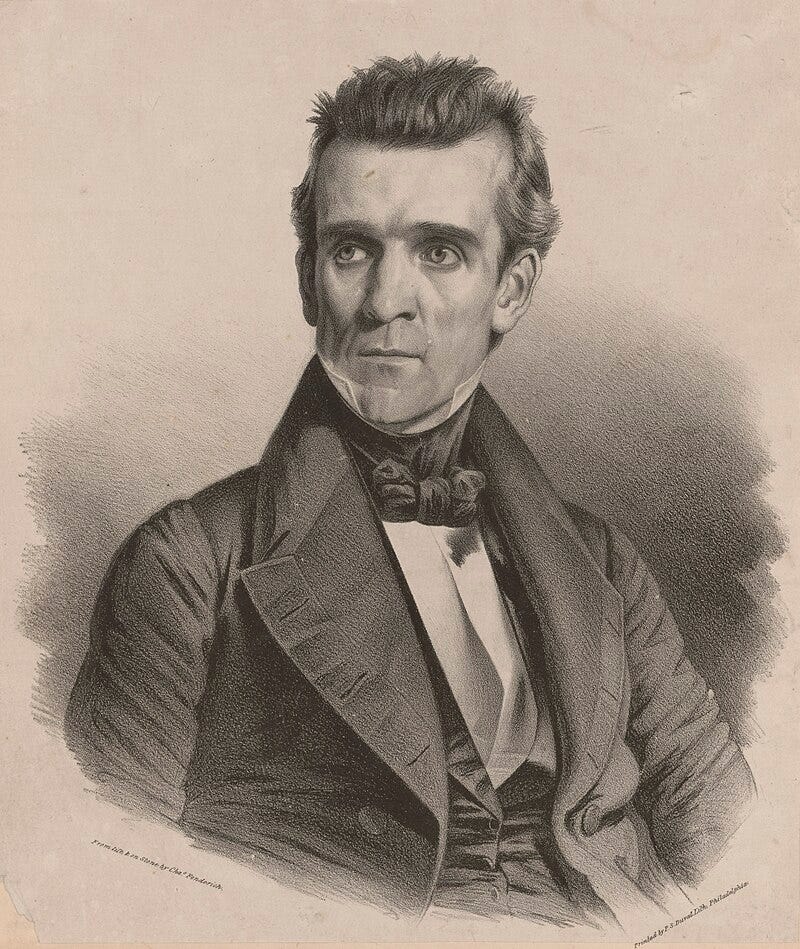

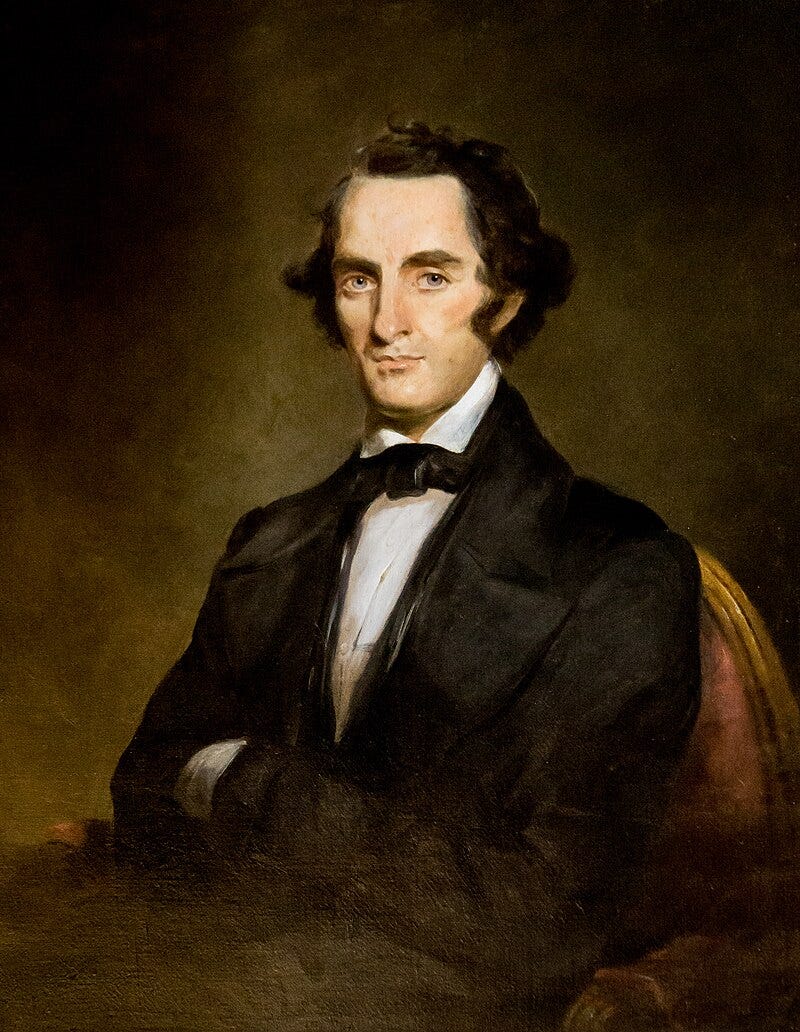

This post has, unsurprisingly, been highly demanded in part due to the relative void of awareness regarding Polk. Polk has always been a lesser-known figure, even among the political Right (this was true even during his time, as he was often referred to as the “Dark Horse Candidate” and later the “Dark Horse President” because he came from relatively humble beginnings). Polk remained a relatively obscure president for several decades after his death; it was not until the early 20th century that he began to pick up traction. In 1910, his diary was made available to the public, and 12 years later Eugene McCormac published his biography of Polk, which finally brought his legacy into the public eye. Not long after, historians began to consistently rank him in the top 10 most important Presidents in American history and he became a frequent topic of discussion when determining presidential success.

The most common talking point surrounding Polk and his administration is that he, unlike arguably any other president, accomplished literally everything he set out to do and then promptly retired from a political life (and then, even more promptly, died 103 days later). Specifically, you will often hear about “Polk’s Four Goals” which are:

Reestablish the Independent Treasury System, which the Whigs had previously abolished after Van Buren established it a few years prior.

Polk reestablished it in 1846 and it lasted until the Federal Reserve was established in 1913, and the last subtreasuries were absorbed 7 years later.

Reduce tariffs, which had become incredibly high primarily due to increasing North-South tensions. Northern manufacturers wanted high tariffs in order to maintain a monopoly on the goods market, while Southerners favored low tariffs for access to cheaper foreign (generally British) goods.

Polk achieved this with the Walker Tariff of 1846.

Acquire part, or all, of the Oregon Country. At this point in time Oregon and the territory that would make up several other future states was claimed by both America and the British. The territories were rather distant for both powers, though moreso for Britain, however the areas strategic importance was clear, especially the natural harbor provided by Puget Sound, which made it highly desirable.

Polk achieved this with the Oregon Treaty in 1846.

Acquire California, and especially its harbors, from Mexico.

This was, of course, achieved with the conclusion of the Mexican-American War in 1848.

These goals were rather lofty, particularly the territorial expansion goals, which doubled the United Sates’ territory even after the Louisiana Purchase. Yet, Polk accomplished all that he set out to do anyway and as you can see, most of what he accomplished was done within the first two years of his presidency, which is even more impressive. These were just the four “main” goals that he promised to accomplish during his campaign, however, and don’t reflect the entirety of Polk’s accomplishments. For example, the Annexation of Texas was sort of a 5th “main” goal (and arguably what won him his election) during the campaign trail. There are some other, more minor, things Polk accomplished as well, such as establishing the Smithsonian Museum and the Department of the Interior. I’ll go into more detail into all of these things in later sections.

Biography

Youth

Like all of the three “Tennessee Presidents” James Knox Polk was actually born in one of the Carolinas, specifically in North Carolina (Andrew Jackson was born in one of the two Carolinas but it’s unknown where exactly he was when he was born, and Andrew Johnson was also born in North Carolina). Like the other two Tennessee Presidents, Polk spent most of his adult life in Tennessee following an early migration once Tennessee attained statehood.

Polk was born on November 2, 1795 in what is now Pineville North Carolina in Mecklenburg County. James’ mother, Jane Polk (née Knox), named the future president after her father, James Knox. While both the Polk and Knox families were Presbyterians, his father Samuel Polk was a deist (something he himself inherited from his own father Ezekiel Polk) and so James was not baptized as a Presbyterian when he was born, as this would have required his father Samuel to have declared his own belief in Christianity. Nevertheless, Jane Polk ended up ultimately winning out and brought James up in a very religious household, solidifying his belief in Christianity. It should be noted, however, that James was a quiet Methodist for most of his adult life and a Presbyterian, but that will be discussed more in later sections.

In 1803, Ezekiel Polk led four of his adult children and their families to what is now Maury County, Tennessee and in 1806 Samuel Polk and his family followed. The Polk family settled mostly in and around the city of Columbia, where they played a strong role in the city’s politics.

James was a rather sickly child for most of his life, until his father took him to see Dr. Philip Syng Physick in Philadelphia (a legendary surgeon and physician for his time, who pioneered many modern techniques and instruments) but the trip was cut short due to James’ immense pain and declining health. Instead, the operation was performed by Dr. Ephraim McDowell in Kentucky (himself a very esteemed surgeon, who also pioneered many modern surgical techniques) who successfully removed the urinary stones which caused James so much pain. For a bit of context, the operation involved essentially slicing into the perineum (the taint) and then scooping them out with something like an sharp ice cream scoop. Of course, the only anesthetic available was brandy. Most historians today suspect that this may have left James impotent and/or sterile due to the damage it likely would have caused, and the fact that James never had any children of his own.

By modern standards, the operation was a “terrifying procedure.” It occurred “under whatever sedation [was] obtainable from brandy.” Jim’s legs were “held high in the air, and being restrained by straps and assistants, the operation was done as quickly as possible. The procedure was to cut into the perineum (the area immediately behind the scrotum and in front of the anus) with a knife and thence through the prostate into the bladder with a gorget, a pointed, sharp instrument designed for this purpose.” The stones then were removed with forceps or a scoop. As able as McDowell was and as quick as he had to be, the procedure must have meant a hellish half hour of sheer torture for Jim Polk, and a recovery period of weeks before he could return home. Considering the crude methodology involved, the probable tearing of ejaculatory ducts, tissue, nerves, and arteries as the gorget penetrated the prostate, there can be little doubt that the operation left him unable to father a child.2

After the surgery, James’ health recovered and he chose to enroll in local Presbyterian Academies in his youth, until he enrolled in the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill where his cousin William Polk was a trustee, and his father Samuel acted as the univeristy’s land agent in Tennessee. Notably, Polk’s roommate at Chapel Hill, William Dunn Moseley, would go on to become the first governor of Florida. Polk engaged in a wide range of academic activities, including the Dialectic society, and graduated with honors in May of 1818.

Early Adulthood

After graduating, Polk began an apprenticeship [law school wasn’t really a thing at this time] with Felix Grundy, a Nashville lawyer of great renown. About a year later Polk was elected clerk of the State Senate, a position he held for three years (1819 to 1822) and his first elected office. In 1820, after 2 years of apprenticeship, Polk was admitted to the Tennessee Bar, and returned to Maury County where he opened a successful law practice. His first ever case was to defend his father, charged with public fighting [based]:

Sam Polk even provided his son with his first case by managing to be arrested for public fighting. James secured his father’s release with a fine of one dollar plus costs, and Sam was instrumental in paying for the construction of a one-room law office and library for his son’s practice.3

The Panic of 1819, which led to a severe nation-wide depression especially in impoverished rural communities like Tennessee, gave Polk a surplus of cases to hone his legal practice with. This successful law practice was also what allowed him to fund his political career, which Polk was now starting in earnest.

Starting in 1822, Polk also began courting his soon to be wife Sarah Childress. Sarah, herself a member of the prominent Childress Clan, was exceptionally educated for a woman at the time, having graduated from the Moravian’s Salem Academy in North Carolina. They first met when they were younger in Murfreesboro Tennessee at the house of Samuel P. Black, where both were receiving instruction, when Polk and Sarah were 19 and 12 respectively. However, they would not be properly introduced until quite a few years later, when Polk was already involved with the State Legislature. It isn’t entirely clear who introduced the two of them, some legends suggest it could have been Andrew Jackson himself as he knew both the Polk and Childress families quite well, and was quite fond of both James and Sarah. It’s also possible that Sarah’s brother, Anderson Childress, could have introduced the two since both he and Polk attended the University of North Carolina. Regardless, the young couple hit it off well and were engaged 2 years later, in 1824.

In 1823, the Tennessee House of Representatives would be holding elections and Polk was determined to win. Polk had a solid voter base to draw from since the Polk Clan was one of the largest and most influential families in Maury County (not to mention the backing of the famous Felix Grundy). Regardless, Polk had an active and energetic campaign. Polk was already a member of the local Freemasons, and he was commissioned as a Captain in the Tennessee Militia’s cavalry regiment, 5th brigade. He was also later appointed Colonel on Governor William Carroll’s staff, which also led to many people referring to Polk by the nickname “Colonel.” These important connections and titles went a long way towards his campaign, but undoubtedly his greatest asset in the election was his natural skill as an orator. Polk’s talent at stump-speaking [old phrase referring to political speeches given locally and often somewhat spontaneously, so named because they were often literally done from atop a tree stump] was so legendary that he earned the nickname “Napoleon of the Stump.” Sarah’s own political skill was also of immense help to Polk at this time, helping him to host large events (Polk himself was quite introverted, whereas Sarah was a socialite of some renown). And, if his immense network of connections, superb oratory skill, and the assistance of his fiancée Sarah all failed to win him the election, Polk made sure to refresh the voters at the polls with a plentiful supply of booze:

By election day, just in case persuasive arguments on the stump had not been enough, Polk paid for “twenty-three gallons of cider, brandy, and whiskey in one election district alone.

What his staunch Presbyterian mother and his fiancée thought of this tactic has gone unrecorded, but such refreshments were a requisite of campaigning, and when the results were tallied, James K. Polk was the new state representative from Maury County.”4

And so, in August of 1823, James K. Polk was elected to the Tennessee House of Representatives as the representative from Maury County, at the age of 27. However, his political career was far from over.

Although all three men where Democrats, Polk began to shift away from the policies supported by Felix Grundy, and instead began to align himself with Andrew Jackson, who was becoming a quickly rising star in Tennessee politics. Jackson had long had close ties with the Polk and Childress family, particularly with the Childresses, and in 1823 Polk cemented himself as an ally of Jackson when Polk broke the deadlock surrounding Tennessee’s Senatorial nomination, leading to Jackson’s victory. This Senate position was crucial for Jackson’s Presidential ambitions, and Polk’s critical role in giving it to Jackson became the foundation of a powerful alliance that would last until Jackson’s death and Polk’s own ascension to the Presidency. In fact, so close was this alliance/mentorship that Polk gained yet another nickname: “Young Hickory,” an homage to Jackson’s own nickname of “Old Hickory.”

“Daughter,” Old Hickory wrote to Sarah Polk shortly thereafter, “I will put you in the White House if it costs me my life!”5

Only a year after his election to the Tennessee House of Representatives, Polk announced his bid for the Federal House of Representatives as the Representative from Tennessee’s 6th Congressional District. This election would be a bit more difficult, as there were now five candidates in total and Polk was campaigning in areas outside of his family-dominated home County. Regardless, Polk was determined to win. In fact, so serious was his dedication to the campaign that his wife Sarah began to seriously fear for Polk’s health. But his dedication paid off. Despite his opponents claims that Polk, at the age of 29, was far too young to handle the responsibility of a seat in the House, Polk won 3,669 votes out of 10,440 beating his four opponents in the process and claiming a seat in the House.

The House

In Washington D.C., Polk became a fierce opponent of the Adams Administration, which was quickly distancing itself from its ties to the Democratic Party. He voted against their policies regularly, gave fiery speeches decrying their positions, and generally became a thorn in their side. After winning re-election in 1827, Polk continued to oppose the Adam’s Administration and eventually became a campaign advisor to Andrew Jackson during his 1828 bid for the Presidency. After Jackson’s victory in the election, Polk became a veritable bulldog for Jackson and was easily one of Jackson’s most important allies, both in the House and in general.

During the “Bank War” [dispute over the re-authorization of the Second Bank of the United States] Polk served as a member of the House Ways and Means Committee, conducting investigations on the Second Bank and issuing a strong minority report opposing the re-authorization of the Second Bank when the Committee voted to renew it. This event undoubtedly shaped Polk’s own Presidential policy regarding the Independent Treasury.

During the Nullification Crisis, Polk initially sympathized with the Calhounite’s opposition to the Tariff of Abominations [most Southerners staunchly opposed tariffs for reasons beyond the scope of this article], however Polk began to distance himself from Calhoun when the latter began to advocate for secession, something that Jackson was famously staunchly opposed to.

After being elected to his fifth consecutive term, Polk (with the support of Jackson) became the chairman of the Ways and Means Committee, one of the most powerful positions in the House. In this capacity, Polk continued to support Jackson’s administration by supporting the withdrawal of funds from the Second Bank, issuing reports questioning the finances of the Second Bank, and supporting Jackson’s policies against the Bank. After the Committee reported a bill to regulate State deposit banks (which later passed), Jackson was able to deposit funds into “pet banks” [a generally derogatory term referring to state banks selected by the Department of Treasury to receive excess funds, basically a kind of proto-Independent Treasury]. Polk then got legislation passed which allowed the Government to sell its stock in the Second Bank, further weakening it.

Shortly after, the Speaker of the House [Andrew Stevenson] resigned to become Minister to the United Kingdom, leaving the position open. Polk, with the support of Jackson, ran for Speaker against three others. However, he was beaten by James Bell, who carried the support of many opponents of the Jackson Administration. However, the position was up for re-election next year and so Jackson began to call in extensive favors in order to support Polk’s bid. Ultimately, Polk defeated Bell in this election and won the Speakership.

As Speaker of the House, Polk became the center of the Democratic Party within the House of Representatives. His wife, ever the socialite, was also instrumental in ingratiating Polk within the social circles of the Capital at this time.

When Martin Van Buren ran for President as Jackson’s chosen successor, Polk continued to support his policies. However, Polk’s allegiance to Van Buren was not nearly as absolute as it was to Jackson, as would soon become apparent in Polk’s own Presidential ambitions. However, Polk was still an ally of Van Buren’s and was instrumental in appointing Democrats to important positions, as well as getting the original Independent Treasury organized and established [though it was soon disbanded, and would be until Polk’s own Presidency].

During his time in the House, Polk never accepted any challenges to duels no matter how seriously his opponents insulted his honor. Incredibly, this drew the public support and respect of Andrew Jackson, who was himself a notorious duelist. Jackson commended Polk’s cool temper and even-handed response to these calls.

Regardless, the Democratic Party was beginning to lose its prestige, primarily because of recent economic downturns and Andrew Jackson stepping out of the spotlight. Polk was beginning to feel the effects too, as he only narrowly won re-election as Speaker during the 1837 election, and doubted he could win again in 1839. By this point, Polk was also entertaining Presidential ambitions and knew that defeat in his re-election as Speaker would be disastrous for his career.

And so, after a total of seven consecutive terms in the House, and two as Speaker, he announced that he would not be seeking re-election. Instead, he chose to run for Governor of Tennessee in the 1839 election.

The Governor

Governorships make for an excellent campaign tool when running for President. By design, the Governor’s office is a State-level microcosm of the President’s office (in fact, many states used to call them Presidents, not Governors). The Governor is the Executive Branch of the State, and a person’s performance in that capacity can reasonably be expected to reflect how they would do as President. Naturally, many politicians with Presidential ambitions seek at least one term as Governor.

However, Polk faced something of an uphill battle in Tennessee. In 1835, the Democrats lost the Governorship for the first time in the State’s history. Tennessee was quickly falling into the newly-formed Whig Party (which later transitioned into the Republican Party and, in that capacity, remained a significant presence for almost a century after until the “Party Swap”). Polk, as head of the State’s Democratic Party, was up against the Whig incumbent Newton Cannon, who was seeking his third consecutive two-year term.

On the campaign trail, Polk masterfully employed his impeccable oratory skills and trounced Cannon in the early debates, leading to the latter’s retreat back to Nashville on “important official business” for much of the campaign. In the final days leading up to the election, Polk crossed the State in order to engage him once more in debates. In the end, Polk’s oratory skills won the State, and he was elected Governor with 54,102 votes to Cannon’s 51,396. In addition, Democrats regained control of the State Legislature and retook three Congressional seats.

Unfortunately, Tennessee’s Governor had limited powers. There was no veto, for example, and patronage was limited by the small size of the State Government. Possibly consequentially, Polk’s three major campaign promises (improved education, regulation of State banks, and internal State improvements) for his Governorship were all rejected by the State Legislature. The only notable success he had as Governor was politicking to replace Tennessee’s two Whig Senators with loyal Democrats.

However, this was less of a concern for Polk who primarily sought to use his Governorship as a foundation for his Presidential ambitions. Specifically, Polk was hoping to be nominated as Van Buren’s Vice President at the 1840 Democratic National Convention in Baltimore. The current Vice President nominee, Richard Mentor Johnson, was disliked by most Southerners for siring two children with his biracial mistress (ewwww), whereas Polk was Andrew Jackson’s star pupil. With Van Buren being a New Yorker, Polk’s Tennessee roots would also help appeal to the South, which was crucial since North-South tensions had been rising for around a decade or two by this point. Ultimately, however, the convention chose not to nominate anyone. Polk withdrew his name.

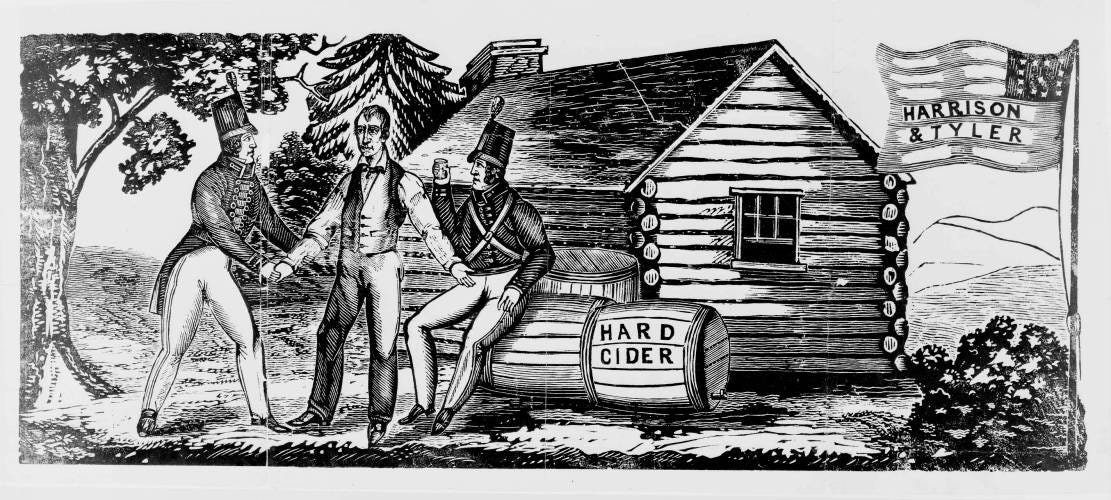

Meanwhile, General William Henry Harrison was conducting a fascinating (and highly effective) campaign for the Whigs. Harrison, born into a wealthy and well-connected family, had become the center of a (nominally) grassroots campaign. Harrison was depicted as a man who would just as soon spend his time at home in a log cabin, sipping cider as he would run the country. As Walter Borneman put it in his biography of Polk, the campaign depicted Harrison and his VP John Tyler as

“two regular guys sitting in a log cabin sipping hard cider and doing what was right for the common man.”6

Harrison himself was also a respected war hero, especially for his victories in the Battle of Tippecanoe and later during the War of 1812. This led to the famous “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too” slogan, which is arguably the most famous political slogan in American history. This campaign, combined with the backlash of the Panic of 1837 and the effect it had on Van Buren’s reputation, allowed Harrison to beat the incumbent Van Buren. But, Harrison’s early death (exactly one month after taking his Oath of Office) from either pneumonia or septic shock, spurred on by his own weakened immune system as a result of regularly failing to heed the weather.

With Harrison’s death, and the shortest Presidential term in history, John Tyler ascended to the office of President of the United States. This was the first time in United States history. Interestingly, this also led many people to claim John Tyler was not a “real President” as he was not truly elected. A fascinating example of this can be seen in a stained glass pane donated by Polk to Columbia’s First United Methodist Church (just across the street from the ancestral Polk Home in Columbia) which refers to Polk as “10th President of the United States,” a title actually possessed by John Tyler, according to modern understandings of the Presidency.

John Tyler’s administration was an interesting one. Most Democrats greatly feared a Whig administration, and may very well have gotten one had Harrison taken better care of himself. However, John Tyler was by no means a party hardliner, and quickly broke from the Whig Party. This, on top of the general novelty of a Vice President becoming President, made his Administration difficult. This would also, crucially, come in to play in the following election.

Returning to Polk’s Governorship; the Whigs were greatly encouraged by the success of Harrison’s campaign. The Whigs sought to retake the Governorship of Tennessee, and were propping up James C. Jones, also known as “Lean Jimmy” to run against the incumbent Polk. This turned out to be devastating for Polk’s career.

Lean Jimmy was basically the perfect foil to James K. Polk, who was 5’8” with an average build, and Lean Jimmy was an insane 6’2” and 125 lbs (that’s 16 BMI btw, actually insane). Lean Jimmy was also known more for his comedic whit than his political knowledge, which allowed him to dance around Polk’s more serious and austere demeanor. Lean Jimmy only advanced basic Whig positions with minimal argumentation, but his clever whit was virtually impossible for Polk to overcome. For the first time ever Polk lost at the polls, and only by 3,000 votes.

Always deferential to the governor, Lean Jimmy evoked part sympathy and part comic relief. After Polk referred to Jones as “a promising young man” but termed his quest for the governor’s chair “all a notion,” Jones was quick to refer repeatedly to Polk—not quite forty-six himself—as “my venerable competitor.”7

Fortunately for the Democrats, Lean Jimmy’s first term was marred by legislative gridlock from the “Immortal Thirteen,” 13 Democratic State Senators who refused to cooperate with the Whigs after the Whigs refused to allow one of the State’s U.S. Senators to be a Democrat. This also left the State of Tennessee unrepresented in the U.S. Senate for several years.

The next election was equally, if not more so, disastrous for Polk and the Tennessee Democrats. After his first defeat in the bid for Governor, Polk returned to his private law practice in Columbia and prepared for the next campaign. Yet, Lean Jimmy once again beat Polk and this time with almost 4,000 votes. Even worse, the Whigs regained control of the State Senate, and ended the gridlock imposed by the “Immortal Thirteen” (likely in part due to the voter’s dissatisfaction with the gridlock, which at least nominally seemed to be the fault of Democrats).

Polk had faced two consecutive defeats in the Gubernational race for his home State. His previously illustrious career seemed to be over, in spite of his legendary performance in the House of Representatives. Most considered James K. Polk to be a lame-duck candidate. The Whigs didn’t view him as a threat, and the Democrats viewed him as a liability.

Then, the unthinkable happened.

The Dark Horse Candidate

By this point, even many of Polk’s close friends, political allies, and advisors were urging him to retire. His political prospects in general were looking rather dour, much less his aspirations for the highest office in the land.

After all, his term as Governor was rather lackluster; he was unable to accomplish much (though this was not entirely his fault), and who was to say he would do better as President? Even more importantly, he had failed to win the vote in the two subsequent elections to a candidate with far less experience.

But Polk himself was entirely unphased. Perhaps it was the legendary stubbornness of the South. Perhaps it was the advice of his close friend and mentor Andrew Jackson. Perhaps it was Polk’s own masterful reading of the political scene. Whatever the cause, Polk still believed he had a shot at becoming the next Vice President of the United States. As we will soon see, that never panned out.

John Tyler, after breaking with the Whigs, had sought the nomination of his old Democratic Party allies. Despite Tyler’s shockingly competent Presidency, his apparently flippant attitude towards Party politics made him an undesirable candidate (Tyler ended up forming a third party, however it was very weak and ultimately failed). And so once again, Van Buren was the Democratic frontrunner for the Presidential election. Once again, Polk sought to be nominated as his Vice President. However, there were a number of alternative candidates who also sought the nomination.

Polk’s recent failures, and the relative popularity of his competition, made this a very uphill battle. Ultimately, even the many letters written to Van Buren by Polk and Old Hickory himself were unable to persuade Van Buren or the Democratic Party to back Polk as Vice President.

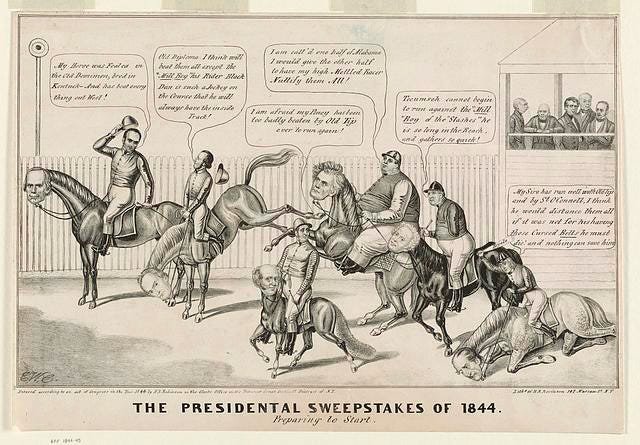

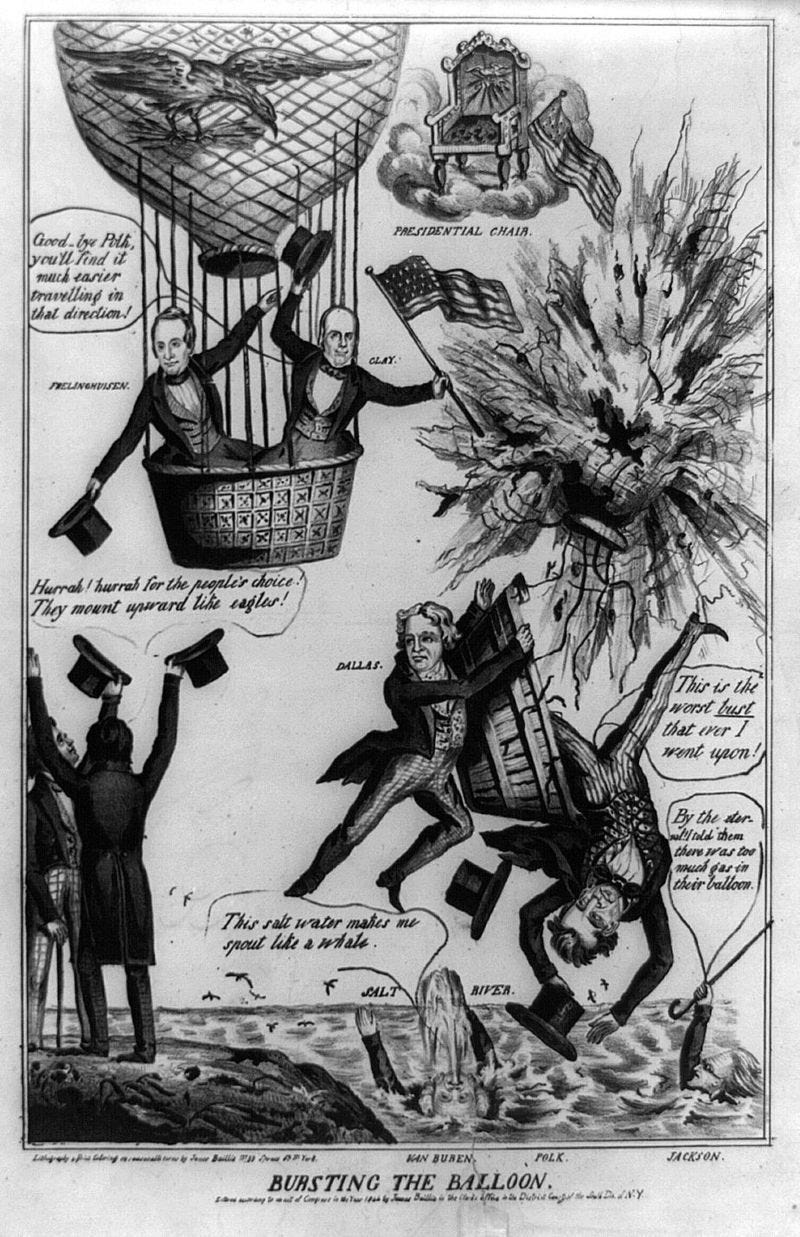

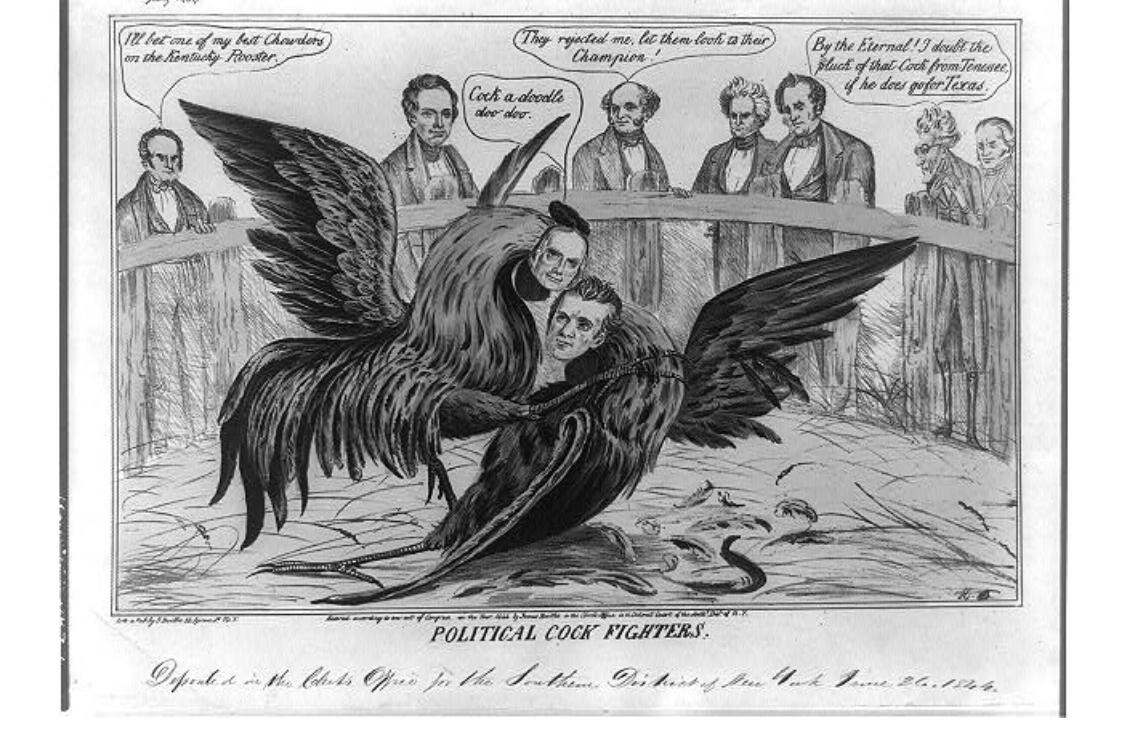

Meanwhile, Henry Clay himself was nominated as the Whig Party’s Presidential candidate. Henry Clay was the Wizard behind the curtains of the Whig Party, and he had long entertained Presidential ambitions, and had run several campaigns before. Many politicians owed their success to Clay’s patronage, and Clay himself was an extremely competent politician. In fact, it is not a stretch to say that Henry Clay may have been the greatest master of Party Politics in America’s history. Suffice it to say, he was a very strong candidate in this election, and many Americans believed this would finally be the year that Clay ascended to the Presidency.

The Texas Question

While these two giants entered the playground, a new issue was quickly rising in American politics: The Texas Question. This would eventually become the downfall of not only Van Buren, but also Henry Clay himself. More importantly, it was Polk’s salvation.

At this point, most Americans desperately wanted to annex Texas. It was seen as an inevitability by virtually everyone, but the slavery debate was stalling its progress. At this point, the Gag Rule and Missouri Compromise had dominated slavery politics for decades, and the strain was showing. Texas would, under the Compromise, be admitted as a slave State, something Abolitionists staunchly opposed. While Abolitionists were not nearly as large a political voice as many people today believe (about as large as the Calhounites, the radical pro-slavery party), they could still swing an election if angered.

In what is probably the greatest political blunder of his career, Henry Clay (a Kentuckian slave holder) announced to the public that he would not be supporting annexation. This delighted Jackson, who was a long time rival of Clay and was still hopeful for the prospects of a Buren-Polk Presidency. But then, Van Buren did the unthinkable: he, too, announced his opposition to annexation. Jackson was devastated.

Almost immediately, Jackson wrote to Van Buren that no candidate who opposed annexation could win this election; it was simply too popular a position. In that same letter, Jackson rescinded his support from Van Buren and instead proclaimed that Polk himself was the best person to head the Democratic ticket. Polk, who had published his own pro-annexation position only four days prior to Van Buren’s announcement, was quickly gaining support from the people as the only real candidate who was pro-annexation.

On top of their blunders regarding the Texas Question, the cracks in the campaigns of both Clay and Van Buren were beginning to show. Clay had a long history of shady politics, and the infamous “Corrupt Bargain” still lurked in the minds of Americans the country over. Van Buren himself had also lost the previous election, despite being the incumbent candidate, which has historically not boded well for Presidential candidates. Van Buren was also facing opposition because of his handling of the Panic of 1837, as well as opposition from Calhounites who feared Van Buren’s more moderate position on slavery.

Incredibly, Van Buren’s position on Texas was published in the Democrats’ mouthpiece, the Washington Globe, on the very same day—April 27, 1844—that Clay’s Raleigh letter appeared in the Whigs’ National Intelligencer. The apparently coincidental same-day publication even raised speculation that these two political veterans had plotted during Van Buren’s 1842 visit with Clay in Kentucky to keep the Texas issue out of the 1844 campaign.8

And so, in the face of this opportunity, Andrew Jackson invited James K. Polk to the Hermitage. Unbeknownst to Polk at the time, Jackson would propose a plan to get Young Hickory, and his dear Sarah, into office. Polk, who was still set on the Vice Presidency as a path to an 1848 Presidency, was utterly shocked at this idea, reportedly calling the plan “utterly abortive.” Nonetheless, Polk trusted his mentor’s wisdom, and he himself knew the Texas Question would make or break this election. And so, Polk instructed his allies in the Democratic Convention to begin spreading the idea of a Polk presidency. Jackson himself began to expend his remaining political capital towards Polk’s election, ultimately exhausting what political resources he still had.

But the stage was not yet set for a public announcement of Polk’s candidacy. Polk and Jackson worked behind the scenes to prepare for this triumph, gathering allies and probing the field. While Polk remained in Columbia, the Democratic Convention was proclaiming full support for Van Buren and still believed Polk sought the Vice Presidency.

Van Buren’s Downfall

As the Democratic National Convention opened on May 27th, 1844 a critical issue came to head: did the nominee need two-thirds of the vote, or a simple majority? Van Buren was almost certainly going to lose on a two-thirds vote due to the extreme opposition he faced on issues of slavery and Texas, but a simple majority was certainly within his grasp. Ultimately, the two-thirds rule was passed.

In the first ballot, Van Buren won a majority but failed to win the two-thirds vote. Van Buren’s support began to dwindle. By the fifth ballot, Lewis Cass (Senator from Michigan) had taken the lead, but he was still unable to break the two-thirds majority. By the seventh ballot, the Convention was hopelessly deadlocked. It seemed that no candidate could break the two-thirds threshold.

This was Polk’s moment.

Gideon Johnson Pillow, one of Polk’s closest allies, had been lying in wait ever since that fateful meeting at the Hermitage. Pillow reached out to another member of the Convention, George Bancroft a longtime correspondent of Polk’s, to propose Polk as a compromise candidate. Just before the eight ballot, a pre-written letter announcing Van Buren’s withdrawal in support of Silas Wright was read to the Convention. In an almost unbelievable twist, Wright had a similar pre-written letter stating his refusal to be considered for the ticket, and thus withdrawing from the race.

Pillow and Bancroft were delighted. Benjamin F. Butler, the man who announced Van Buren’s withdrawal began to rally support behind Polk. When the 8th Ballot was counted, Polk only had 44 votes, with Cass and Van Buren (who had not yet been officially removed) still at the top, thought it seemed that the deadlock was soon to break. Butler formally withdrew Van Buren’s name before the ninth ballot, which ended in a resounding 233 votes for Polk, and only 29 for Cass. Afterwards the nomination was made officially unanimous, and Polk became the Democratic candidate for the election of 1844.

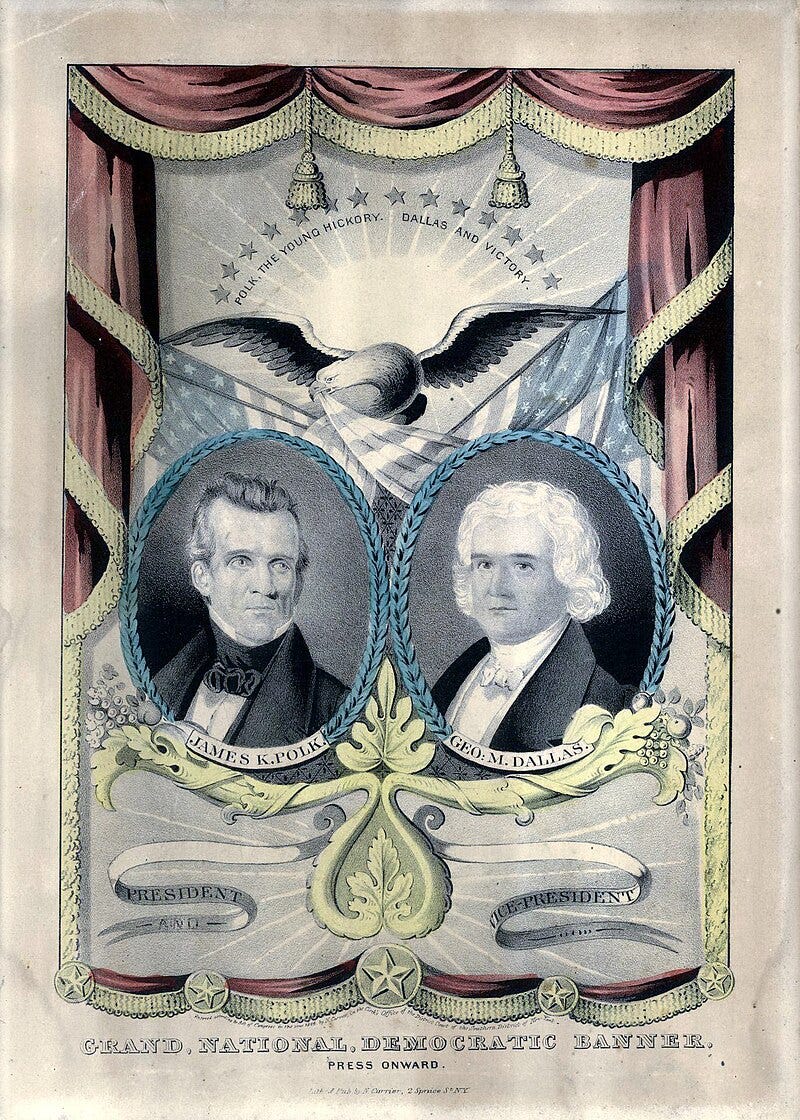

Silas Wright was initially considered for the Vice Presidency, but after he refused an almost assured nomination for President, he similarly refused the Vice Presidency. Ultimately, George M. Dallas was selected and thus the Polk-Dallas ticket was formed.

In later years, there was no shortage of men who claimed to have been the leading proponent and chief strategist of Polk’s nomination for the presidency. Cave Johnson, Gideon Pillow, George Bancroft, Benjamin Butler, and others undoubtedly played important roles, but the two who had done the most were back in Tennessee, one an aging icon ensconced at the Hermitage and the other a shrewd life-long politician waiting expectantly in Columbia.9

In response, the Whig Party coined the simply slogan “Who is James K. Polk?” as their rally cry against the “Dark Horse Candidate.” In reality, Polk had a an extensive political career and long been a thorn in the side of the opponents of the Democratic Party. Regardless, all prior presidency had either been Vice President, Secretary of State, or a legendary General prior to ascending to office. No President, before of since, had been Speaker of the House, the highest position Polk had held prior to the Presidency.

But one man knew not to underestimate James K. Polk: Henry Clay.

The Campaign Trail

After receiving word that he was officially nominated for President, Polk made an official announcement proclaiming he had never intended to run in this election and that he intended only to serve a single term. Polk remained in Columbia, giving no speeches, but remained in correspondence with Convention leaders as they organized the campaign. However he did publicize his views in the form of responses to citizen inquiries, so as to establish his platform.

One of the other pressing issues of this election, and something which would become a pillar of Polk’s administration, was the tariff. At the time, tariffs were the primary source of funding for the federal government and it was heavily debated whether the primary purpose of the tariff should be to procure this funding, or if protectionism was an acceptable reason. Northern voters favored economic protectionism due to their manufacturing focus, but the South preferred lower tariffs in order to widen the market with cheap foreign (British) goods which would ease the burden on the poorer rural communities. Polk stood to gain or lose a lot of support based on his position and, knowing this, he referred back to his long support of tariffs as a source of finances, but maintained that they could also offer protection to American interests. Polk’s careful answer, which toed the line between the North and South, infuriated the Whig Party, who sought to trip up his campaign by pressing Polk on the tariff.

Inside the Democratic Party, John C. Calhoun and his followers were still not convinced of Polk’s position. But when Calhoun sent a friend and former Congressman from South Carolina (Francis Pickens) to meet with Polk and Jackson, he was reassured that Polk would do well.

Meanwhile, incumbent Tyler was still running as a third party candidate. His party, which had significant overlap with the Democratic Party, threatened to split the vote and potentially cost Polk the election. Tyler had no illusions about actually winning, but he knew he could maintain some personal power due to the not inconsiderable position he was in. Seeking to resolve this, Andrew Jackson wrote two letters to friends he had in Tyler’s cabinet. In these letters, Jackson promised that Tyler’s supporters would be welcomed back into the Democratic Party proper, and that Tyler himself would be welcomed back with open arms for his pro-annexation stance. Jackson was also able to exert influence over the Globe newspaper, the party paper for the Democratic Party, in order to stop an attacks on Tyler.

Hindsight was beginning to bite at Henry Clay, who was beginning to realize the gravity of his failure to support Texas annexation. In an attempt to rectify this, Clay published letters to clarify his position on the Texas Question. Yet this turned out to be only another faux pas, and caused uproar at Clay’s perceived insincerity. So unpopular was this position that even a few Southern Whig leaders threw their support behind Polk, due to his pro-annexation stance.

In a final attempt at kneecapping the Polk campaign, the Whig party published a fictional story, now known as the Roorback Forgery, in the abolitionist newspaper the Ithaca Chronicle. In this story, which was not published as fiction, the fictitious German Nobleman Baron von Roorback purported to have seen forty slaves sold by Polk, after having been branded with his initials. The story was later withdrawn, but not before it was widely circulated. Fortunately, it was not quite as devastating as the Whigs had hoped. For one, it reminded Americans that both Clay and Polk were slaveholders. On the other hand, Southerners saw Polk has a hero of paternalism and staunchly defended him.

In November of 1844, Polk won the election with 49.5% of the popular vote and 170 out of the 275 possible electoral votes. However, he was the first President to lose his home state (he also lost his birth state of North Carolina). At the same time, he beat out Clay in New York and Pennsylvania, where the Liberty Party (a radical abolitionist party) split the vote. Crucially, Polk would have lost the election had he not won New York.

The Presidency

Polk ascended to the Oval Office during a time of immense growth and development in America, but also one of great sectional division. America was quickly becoming a peer with Great Britain, but sectarian tensions between North and South loomed behind every corner.

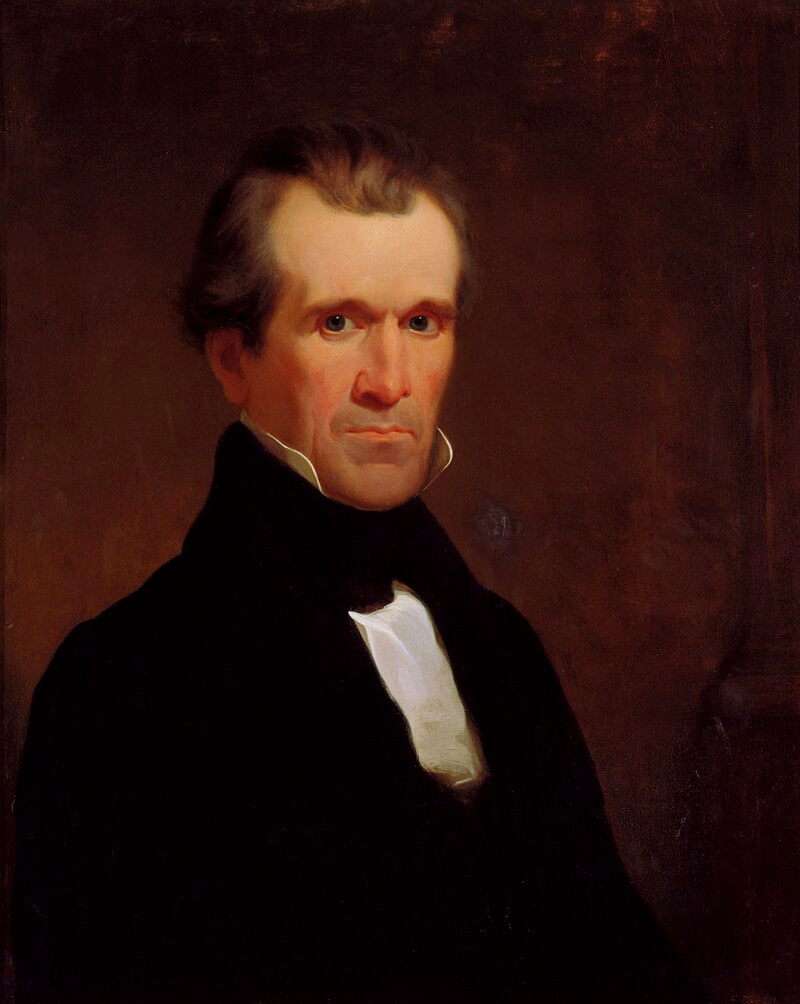

With Jackson’s help, Polk assembled his administration and began the long road towards achieving his goals. At forty-nine, Polk was the youngest President in U.S. history. That didn’t stop Polk from putting in the long hours. Even before his inauguration, Polk adamantly proclaimed “I intend to be myself President of the United States” a stance he faithfully held for the duration of his Presidency. Polk would work ten to twelve hours a day, toiling over his desk with little vacation time.

Friday, 29th December, 1848

Many matters of minor importance and of detail remain on my table to be attended to. The public have no idea of the constant accumulation of business requiring the President’s attention. No President who performs his duty faithfully and conscientiously can have any leisure. If he entrusts the details and smaller matters to subordinates constant errors will occur. I prefer to supervise the whole operations of the government rather than entrust the public business to subordinates, and this makes my duties great.10

The Oregon Territories

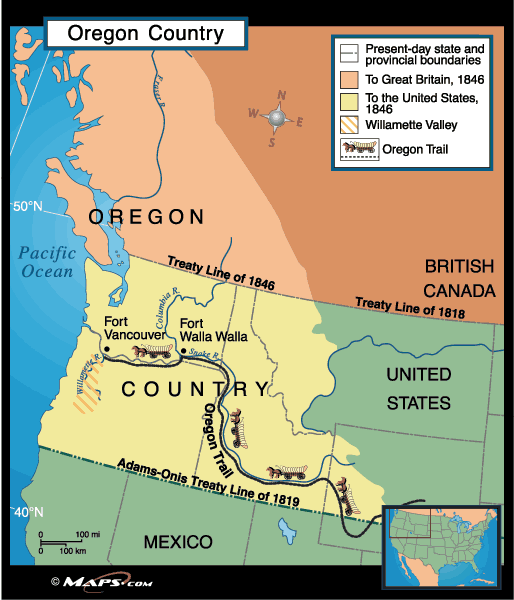

Many nations had claimed the Oregon Territories, following previous expeditions to the land, but by 1846 only Britain and America stood by their claims. However, the land was still too distant from both American and Britain for it to be a top concern for either. Nonetheless, American settlers were steadily pouring into the Oregon country at this time.

Prior efforts to settle the Oregon Question had revolved around a partition at the 49th parallel, but Britain was unwilling to accept this due to its significant commercial interest along the Columbia River and a strategic interest in Puget Sound. Similarly, America was unwilling to let go of Puget Sound because of the immense strategic value it would have on naval activity in the Pacific.

Meanwhile, American interest was skyrocketing. While the Texas Question dominated election debates in 1844, settlers were piling in to Oregon and demanding American protection. In fact, many were calling for annexation of the entire Oregon Territory, all the way up to 54 degree, 40 minutes North latitude.

Publicly, Polk proclaimed America’s “clear and unquestionable” claim to Oregon. Privately he knew that it was not worth a third war with Britain, who had already warned America that they would take military action if America attempted to claim all of the territory. This was particularly problematic, as American had already entered into war with Mexico in April of 1846 and the threat of a two-front war against both Mexico and Britain would comprise America’s interests in both territories.

With negotiations failing to provide fruit, Polk gave Britain a one year notice (as was required by Treaty) that he intended to terminate the joint occupancy and administration previously enjoyed by Britain and America. In doing so, Polk employed the Monroe Doctrine to defend his position, the first time the Doctrine was employed since its inception in 1823.

Now, with the ball in Britain’s court, Polk required the British to make the first move. In response, the British offered a division at the 49th parallel, excepting that Britain maintain full control of the entirety of Vancouver Island and would retain temporary and limited navigation rights to the Columbia River. Polk accepted this offer, and the Senate ratified the Oregon Treaty in a 41-14 vote on June 15, 1846.

Many commentators have noted that Polk’s stubborn negotiation tactics likely awarded America greater concessions than we would have otherwise acquired. Additionally, Polk’s alterations to the tariff (which caused a massive boom in American-British trade) made the British reconsider risking war with America over a distant territory, thereby losing the immensely beneficial trade partnership in the process. Whether or not this was according to Polk’s plan is unclear, but his shrewd political senses leave it reasonable to assume that Polk was well aware of the impact his relatively mundane domestic policy would have on his ambitious foreign policy goals.

Domestic Policy

Polk’s domestic policy was quite typical for such an adamant Jacksonian. Despite his expressed neutrality on the topic of the tariff during the campaign trail, lower tariffs were popular among Jacksonians and Southerners. Being that Polk was both a Jacksonian and Southerner, it is not particularly surprising that one of his first major accomplishments was signing the Walker Tariff into law (July 2, 1846), which substantially lowered the tariff rates from the previous “Black Tariff” of 1842.

While the tariff may, today, seem like the most boring or simple accomplishment Polk made during his Presidency, it actually was one of the most critical policies he held. Explanation requires a slight digression into both the past and near future of Polk’s Presidency, however. Since our country’s inception (and basically until the formation of the IRS in 1862) tariffs were the lifeblood of the Federal Government. Today, tariffs are almost exclusively a diplomatic tool used to leverage international actors and protect domestic interests (this stems primarily from the Reciprocal Tariff Act of 1934). However, during Polk’s time (and long after) the tariff was seen primarily as a fundraising tool, and its power to protect American interests was hotly contested, from both legal and economic perspectives.

To put it generally, the North favored high tariffs because it offered protection to the growing American industry, which was primarily located in the North. Conversely, the poorer and less developed agrarian South favored low tariffs in order to have access to cheap British goods (who could produce them more efficiently than the still young Northern industry). Thus, the tariff was the principal issue around which the growing North-South tensions boiled.

Growing tensions over slavery and several other issues which could be generally divided along a North-South axis were, unsurprisingly, causing immense civil unrest. The tariff in particular caused great turmoil as it was wildly inconsistent in application. Unlike policy on slavery, which remained consistent if nothing else, the tariff was changed every few years, often times multiple times within the same decade. Each change shifted the burden between impoverished Southern consumers and aspiring industrialists in the North. A balance was virtually impossible, and when one was found it seldom ever lasted. And, due to the fact that tariff was how the Federal Government funded itself, it was an issue that was impossible to avoid.

In this sense, the Walker Tariff that Polk passed is rather insignificant in the grand scheme of things. It didn’t resolve the dispute over the tariff in the same way that the establishment of the IRS did. Yet, it also began an era of increasingly low tariffs as Democrats controlled Congress. Consequentially (and due in part to similar reform in Britain) foreign trade boomed at this time, and actually led to an increase in funding, despite the lower tariffs.

Polk’s other major domestic policy was the re-establishment of the Independent Treasury. As mentioned in previous sections, Polk was instrumental in getting the first Independent Treasury established when Van Buren was President. He was also one of the most ardent critics of the national banks that immediately preceded and succeeded Van Buren’s Treasury.

In his inaugural address, Polk clearly stated his opposition to national banks and reaffirmed his intent to establish the Independent Treasury. After passing through the House and Senate (passing without even a single Whig vote in either), Polk signed the Independent Treasury Act into law on August 6, 1846. From then, it lasted until the Federal Reserve Act of 1913. While the history of American banking, and the significance therein, is a topic for another day, I think most of us agree that the Independent Treasury was preferable and that things have, generally, taken a turn for the worse since its abandonment.

The Mexican-American War

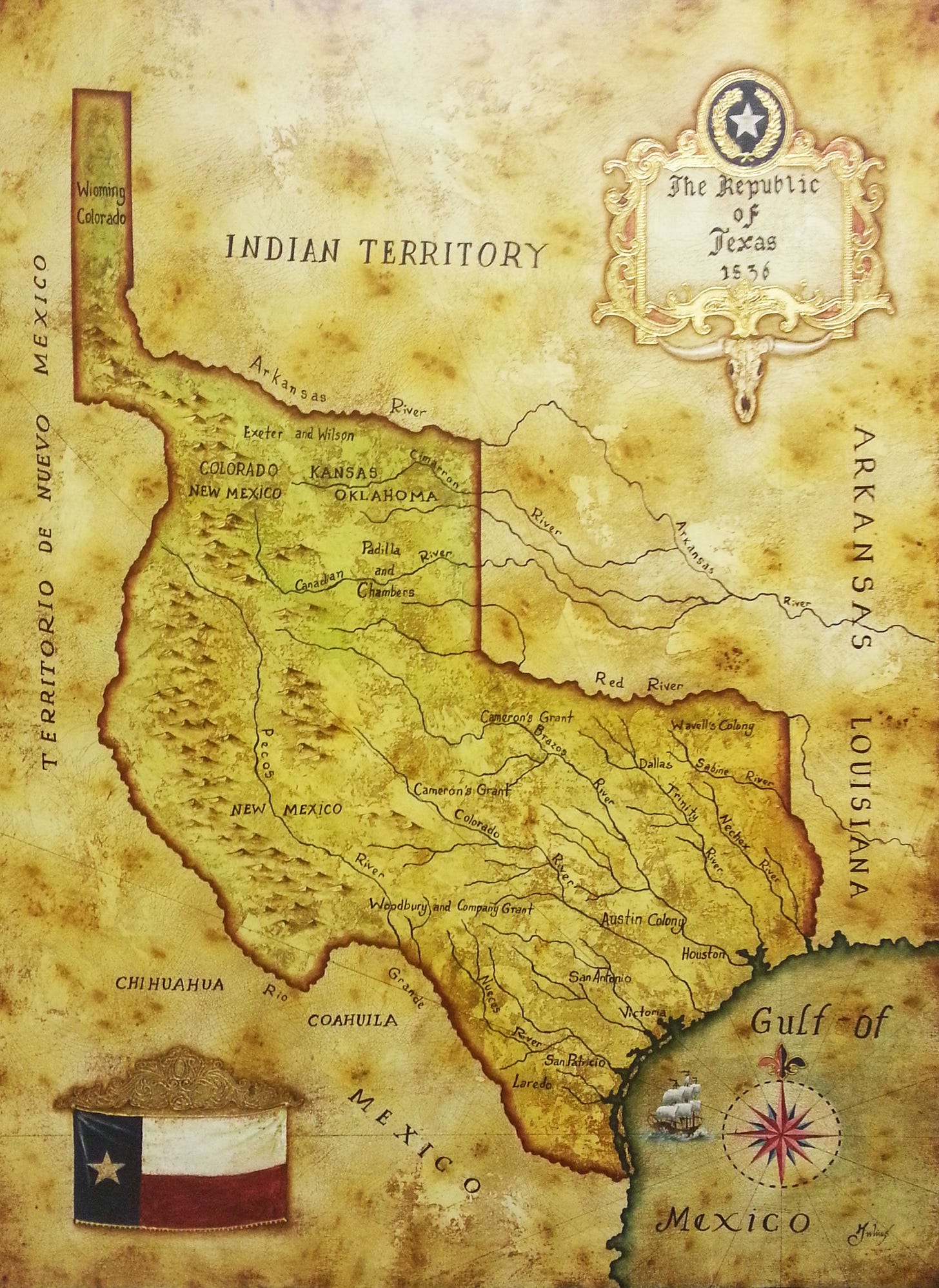

After having declared independence from Spain, Mexico came to possess a significant portion of North America. However, Mexico was plagued by civil unrest following their independence. Several civil wars and coups occurred between independence and the Mexican-American War, and this made it extremely difficult for Mexico to project its power into lands outside of its core territory (essentially what is today modern Mexico, though more heavily concentrated on the larger cities). In fact, most of the land that America came to acquire after the War was virtually uninhabited, as Mexico could not sustain the administrative network necessary to support such efforts.

Faced with a population that had doubled every 20 years since its founding, and presented with wide tracts of Mexican land that was virtually empty, Americans had their heart set on acquiring these new lands. This impulse was further exacerbated by the claims maintained against Mexico by the Republic of Texas following its independence (the history of which is broadly similar to the leadup to the Mexican-American War itself). Ultimately these desires, driven by a decades long “Sea to Shining Sea” Manifest Destiny impulse, caused the American government to take action.

Polk did not initially plunge the country into war, but he was not opposed to the idea and was cautiously preparing for it. Instead, his first offer was to purchase New Mexico and California for $30 million [approximately $1 billion today] with the added caveat that Mexico recognize the Rio Grande as a border (this was in dispute since Texas’ independence).

From here, the waters have been greatly muddied by modern (and, to some extent, contemporary) anti-Manifest Destiny/anti-Imperialist sentiments, and of course the fact that Mexicans are brown and therefore wholesomechungus, whereas Whitey is evil.

John Slidell was the diplomat sent to make this offer, however the Mexican government refused to receive him and expressed hostility at the idea. Then Mexican President José Joaquín de Herrera was soon overthrown by a military coup led by General Mariano Paredes, who was dead set on retaking Texas by force. Official correspondence indicates that Slidell believed war with Mexico was a certainty, regardless of America’s position.

Meanwhile, Brigadier General Zachary Taylor (who was also Polk’s Presidential successor) had arrived at the Rio Grande after being sent there by Polk in preparation for a potential war. After setting up camp, Taylor received word from a Mexican General, Pedro de Ampudia, demanding that Taylor return North to the Nueces River.

America claimed the Rio Grande as its border with Mexico, and Mexico claimed the Nueces River as its border (though many still viewed Texas a illegitimately American). After General Taylor refused to leave, Mexican forces crossed the Rio Grande. Upon hearing reports of their crossing, General Taylor (who had standing order to avoid provocation, but respond to any aggression accordingly) sent two small expeditionary forces to investigate. One of the expeditions, approximately eighty men led by Captain Seth B. Thornton, rode directly into a Mexican ambush. The Mexicans (numbering 1,600) greatly outnumbered the much smaller American force, and killed or captured everyone. This event became known as the Thornton Affair.

This is crucial to understand, as many modern leftists (especially scholars) while construe this in such a way where America is clearly the aggressor; where America clearly encroached upon “Mexican” lands to deliberately provoke war. The reality is much less simple, and arguably paints Mexico in a worse light. To state it clearly:

The Nueces Strip was genuinely claimed by both countries and had been for years at this point. Neither country could claim ignorance of the other’s claims, so this isn’t exactly “Mexican” land any more than Texas was “Mexican” land at this point.

Any comment that America should have expected a Mexican response to setting up camp in the Rio Grande can be easily met with the fact that Mexico knew exactly what was going to happen if they took action themselves. If you have a border dispute, the only way to settle it is through war or diplomacy. It doesn’t just go away. The acquisition of the Oregon Territories is an example of this.

Mexico itself was already preparing for war in order to reclaim Texas and, if they had won, would have certainly pursued that goal. This is not a clear cut defensive war, but rather a mutual border dispute and a contest of territorial ambitions. Hardly unusual.

Regardless, after Polk was informed of the attack on Taylor’s men he was livid. He immediately sought a declaration of war from Congress. In his address to Congress, he stated:

The cup of forbearance had been exhausted even before the recent information from the frontier of the Del Norte. But now, after reiterated menaces, Mexico has passed the boundary of the United States, has invaded our territory and shed American blood upon the American soil. She has proclaimed that hostilities have commenced, and that the two nations are now at war.11

As many of you likely know, Abraham Lincoln infamously opposed this declaration. Specifically, he essentially questioned the validity of America’s claims to a border at the Rio Grande, through the infamous “Sport Resolutions.” At the time, these resolutions were largely ignored by the House but have since formed the basis for any criticism of the Mexican-American War. I would highly recommend, if you are interested, to read Polk’s own Congressional address [see above footnote] in full and decide for yourself. The address itself states, in no uncertain terms, that the attack occurred in the Nueces Strip. There is no attempt to obfuscate that fact.

The actual course of the war is quite lengthy and generally beyond the scope of this post, but covered in detail in many of the books listed below for anyone interested. Generally speaking, American forces swept away Mexican forces throughout the war. In virtually all engagements, Mexican forces were trounced by Americans, with greatly disproportionate casualties between the two. Notably, there are numerous instances of Mexican forces abusing armistices, perfidy, and peace talks to gain an advantage over the Americans. This never really worked in their favor and generally only angered Americans further due to the dishonorable conduct. Ultimately, more Americans died from diseases than combat.

Famously, Polk miscalculated in allowing Santa Anna to return to Mexico. Polk had hoped that Santa Anna (who had been in exile) would be able to head a Mexican Government that would be amicable to a treaty with the U.S. Indeed, Santa Anna had expressed as much to Polk, however when he returned to Mexico he instead mounted a defense which prolonged the war by as much as a year.

Generally, the overwhelming support for the war in the early days began to wane. Disease was taking its toll on the troops, wartime expenses were mounting, and the war was generally dragging on longer than Polk had anticipated.

Eventually, America won and the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed on February 2, 1848. In that treaty, Mexico ceded 55% of its current territory to America, released all claims on Texas, and recognized the Rio Grande as the proper border between the two countries. In exchange, America paid Mexico $15 million (diplomats were authorized to offer up to the original $30 million) and accepted all debts owed to Americans by the Mexican government. Additionally, any Mexicans living in the territory were permitted to either stay and receive American citizenship and all the rights it entailed, or freely return to Mexico.

A number of famous alternatives to the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo were presented. Some, such as Henry Clay, advocated for no more than a settlement of the Nueces Strip border dispute. Others advocated for the annexation of the entirety of Mexico. Grey areas developed in-between, and Baja California was almost annexed but Polk feared Mexico would reject such a demand and he was unsure that the now Whig-dominated Congress would approve of an extension to the war. Notably, at least among our circles, was the argument that complete annexation should be opposed on racial grounds. Most famously espoused by John C. Calhoun:

To incorporate Mexico, would be the very first instance of the kind of incorporating an Indian race; for more than half of the Mexicans are Indians, and the other is composed chiefly of mixed tribes. I protest against such a union as that! Ours, sir, is the Government of a white race.12

“Minor” Accomplishments

As mentioned in the very beginning, Polk accomplished a great deal more than his “four pillars” that are commonly known. I’ll go over them briefly here, as many of them are rather significant.

Texas

Strictly speaking, even though Texas was the issue upon which Polk was elected it was not entirely his efforts which saw annexation come to fruition. John Tyler had laid much of the groundwork for annexation, but was not able to complete it before his term was over. However, the resolution signed by Tyler prior to the end of his term allowed the incoming President to choose between approving annexation or returning to negotiations. Of course, Polk campaigned extensively on his pro-annexation stance and immediately set out to facilitate Texan statehood. Polk assured Texans that he would send forces to defend Texas, retain the border at the Rio Grande, and offer Texas statehood as the 28th State. After ratification by Texan citizens, this came into effect. However, Mexico broke diplomatic relations with America as a result of this, as Mexico had never recognized Texan independence.

Department of the Interior

On March 3, 1849 Polk established the Department of the Interior. However, as a staunch Jacksonian, he expressed strong private concerns about enabling the Federal Government to exert power of the public lands of the various States.

The Smithsonian and Polk Museum

On August 10, 1846 Polk signed into law an Act which established the Smithsonian Institution. James Smithson, an Englishman would had never been to America, had initially bequeathed his entire estate (totaling 1/66 of the entire federal budget) to the United States government under the mandate “for the increase and diffusion of knowledge.” Andrew Jackson himself announced this bequest to Congress, which was accepted on July 1, 1836 (roughly seven years after Smithson’s death). Unfortunately, the rather vague nature of this bequest and the general anxiety surrounding Federal spending led to intense debate over the scope of this project, and it would go unsettled until Polk signed the Act into law.

To this day, the humble James K. Polk Museum in Columbia Tennessee enjoys a special relationship with the Smithsonian because of this. The Polk Home is often host to a number of traveling Smithsonian exhibits, generally related to Polk in some way.

Polk himself was an avid student of history, behind closed doors, and had a strong desire to leave his mark on history. Initially, he intended to live out his retirement with his wife Sarah in their Nashvillian mansion, The Polk Place, which was to be converted into a museum on the passing of Polk and his wife. Unfortunately, since Polk had no children of his own, a complicated legal dispute arose after the death of Sarah in 1891. Sarah had unofficially adopted her great-niece Sarah “Sallie” Polk Jetton Fall, who was willed the estate by the late First Lady. However, other Polk relatives disputed the claim and a lengthy legal dispute followed, which ultimately sided against Sallie Polk. The Polk relatives had no desire to follow James’ will, but could not decide what to do with the property. At one point, the State nearly acquired the estate for use a Governor’s Mansion, though this never came to fruition. The Tennessee Supreme Court eventually ordered the family to sell the property and split the proceeds in 1900. One Jacob M. Dickinson purchased the house, and sold it to a developer who eventually demolished it in order to build an apartment building. Now, The Capitol Hotel occupies the plot.

Thankfully, Sallie Polk refused to give up and fought to carry out the will of James and Sarah Polk. During her time at the Polk Place, she frequently opened her home for tours by the public and, once the Polk Place was destroyed, she fought to relocate the museum to its present location in Polk’s hometown of Columbia. With the help of her daughter, Saidee Grant, Sallie founded the James K. Polk Association in 1924. Five years later, Saidee purchased the home alongside the State of Tennessee and moved the remaining contents of Polk Place to the house, for purposes of display.

Since then, there have been numerous efforts to relocate James. K. Polk’s tomb to his home and museum in Columbia. It was his initial wish, per his will, to be buried at Polk Place. Initially it was so located, however his tomb was moved to the State Capital in 1893. Since then, there have been efforts to relocate his tomb to his home in Columbia. The reasoning goes that Polk’s wish was to be buried on the grounds of his former home, which was to be converted into a museum for the public. Since Polk’s family, excepting Sallie and her daughter, failed to uphold his wishes the Polk Home and Museum in Columbia is the most appropriate place to let Polk rest. These efforts are currently ongoing, with things generally moving slowly in the direction of relocation.

The Gold Rush

The California Gold Rush began in the last days of Polk’s term. Initial, and somewhat unreliable, reports indicated the presence of significant gold deposits in the newly acquired territories. In Polk’s final address to Congress, he proudly announced verified reports of gold in California and later provided actual samples of the gold. Polk was delighted by the discovery and saw it as a kind of divine validation of his expansion.

In his final days in office, Polk witnessed the large influx of immigrants to California, sparking the California Gold Rush.

Death

Many of Polk’s allies urged him to renege on his prior single-term commitment, and there is some speculation as to how seriously he entertained the idea, but Polk ultimately declined to do so.

On March 3, 1848 Polk left the Oval Office. Entirely unsurprisingly, Polk left a clean desk and spent his last days in the Capital working on appointments and bill signings before officially retiring. He and Sarah immediately embarked on a triumphal tour of the South, which was to ultimately end in Polk Place in Nashville.

Unfortunately while on this tour, Polk was taken ill with a severe cold. A passenger on Polk’s riverboat died of cholera, and Polk became deeply concerned for his health. It was, however, too late to alter course and Polk arrived in Louisiana. It was his intention to quickly depart, but Louisianan hospitality reportedly delayed his departure. On his way North, several more passengers died of cholera and Polk himself had to go ashore and rest due to his grave illness.

After arriving in Nashville, Polk seemed to be on the mend. However, just a few months later he took ill again. Finally, after being baptized in the Methodist Church, Polk died on June 15, 1848 a mere three months (103 days) after leaving office. Tradition holds that Polk’s last words, spoken to his wife, were: “I love you, Sarah, for all eternity, I love you.” Sarah would go on to live another 42 years, never remarrying.

Significance

But it’s a net loss to have the Boers migrate out of the land their ancestors tamed and built, and it would be a net loss in America if it had to happen what some of you want, to cede the southwest to Mexico, or whatever other schemes are discussed. If indeed you do manage to get a white population that is as mobilized and self-aware as you want, they won’t feel it a great victory to give up land and resources their ancestors won by their valor. The greatest president was Polk.13

Among our circles, Polk’s significance is quite clear. Through his Presidency, Polk added the most landmass to the United States of any single President, and the vast majority of this land was added through the conquest of Mexico. Polk was also responsible for the (re)establishment of the Independent Treasury, which has a special place in the hearts of many Right Wingers, as it was the predecessor to the Federal Reserve, an institution that many of us believe has placed us firmly under the heel of (((foreign interests))), just as Polk and the other Jacksonians had feared would happen in their time.

Polk’s Presidency itself was also of a legendary character. Veni, Vidi, Vici summarizes Polk’s administration just as completely as it did Caesar’s conquest. Yet, at the same time, he displayed the humility of Cincinnatus. He accomplished things few other Presidents can claim, in only a single term and without seeking re-election.

Polk’s best attributes are also illustrated in the short comings of his opponents. “Lean Jimmy,” while charming and charismatic, was not the most politically astute when it came to actual matters of State. Henry Clay, probably this greatest practitioner of Party Politics the United States has ever seen, was too disingenuous and more interested in the Prestige of the Presidency than the responsibility. Polk, on the other hand, took this responsibility very seriously.

For some, namely those in the Vitalist crowd, Polk also exemplifies their ideal of a short, though glorious, life. Polk, in his one term, was able to accomplish Greatness, and then promptly died. He never truly knew the degradation of age, only the glory of youth.

It’s no wonder, then, that so many in our sphere admire Polk. Bronze Age Pervert, in the quote at the beginning of this section, called him “the greatest President,” James Kirkpatrick [Kevin DeAnna] uses Polk’s first name and portrait as part of his pseudonym online, and of course yours truly.

It’s a great shame, then, that no good biopics of Polk’s life exist. His life would make for an excellent story on the big screen. I think someday I would like to have a part in making this happen.

Selected Quotes

All of the quotes included in this article were included deliberately, generally because I think they reveal important details about Polk’s character. However, not all of the quotes I have selected could be easily fit within the rest of the article, and so I leave them here.

Some years later, after their political views had diverged, [Davey] Crockett poked a little fun at Polk and perhaps himself by recounting how in the course of that ride Polk had expressed to Crockett his opinion that the legislature was likely to enact changes in the state’s judiciary. “Now so help me God,” Crockett later wrote in his autobiography, “I knew no more what a ‘radical change’ and a ‘judiciary’ meant than my horse, but looking straight into Mr. Polk’s face as though I understood all about it, I replied, ‘I presume so.’”14

That young Polk was a stickler for detail became apparent early. When Jackson protégé Sam Houston, who was then practicing law in Nashville and who would later achieve enduring fame in Texas, sent Polk a judgment from a North Carolina court for execution in Tennessee, Polk rejected it. Finding the paperwork “incomplete, and not authenticated in the manner required,” Polk advised Houston not “to commence an action on this record” until it was corrected. (In their demeanor, Polk and Houston were polar opposites, and Houston is supposed to have once observed that Polk was “a victim of the use of water as a beverage.”)15

Sarah, no doubt, was upset by this intrusion on a Sunday, and even Polk recorded in his diary that only Black’s urgent insistence had gotten him to depart “from my established rule to see no company on the Sabbath.”16

Further Reading

James K. Polk

Polk: The Man Who Transformed the Presidency and America, Walter R. Borneman

James K. Polk, John Seigenthaler

James K. Polk: A Clear and Unquestionable Destiny, Thomas M. Leonard

The Presidency of James K. Polk, Paul H. Bergeron

Slavemaster President: The Double Career of James Polk, William Dusinberre

James K. Polk and the Expansionist Impulse, Sam W. Haynes

James K. Polk: A Political Biography, Eugene Irving McCormac

to the Prelude to War 1795-1845

to the End of a Career 1845-1849

James K. Polk, Charles Sellers

Jacksonian, 1795-1843

Continentalist, 1843-1846

James K. Polk: A Biographical Companion, Mark E. Byrnes

The Life of James Knox Polk, John S. Jenkins

Lady First: The World of First Lady Sarah Childress Polk, Amy Greenberg

Mexican-American War/The Oregon Question

For Duty and Honor: Tennessee’s Mexican War Experience, Timothy Johnson

A Country of Vast Designs: James K Polk, the Mexican War, and the Conquest of the American Continent, Robert Merry

The Diplomacy of Annexation: Texas, Oregon, and the Mexican War, David M. Pletcher

Manifest Ambition: James K. Polk and Civil-Military Relations during the Mexican War, John C. Pinheiro

The War with Mexico, Justin H. Smith (Vol. 1 and 2)

Mr. Polk’s Army: The American Military Experience in the Mexican War, Richard B Winders

A Wicked War: Polk, Clay, Lincoln and the 1846 U.S. Invasion of Mexico, Amy S. Greenberg

Primary Sources

Correspondence of James K. Polk (14 volumes, at time of writing), Wayne Cutler et al.

The diary of James K. Polk during his presidency, 1845 to 1849 (4 volumes), Milo M. Quaife

Discussion

I can’t say I’ve read all of these books, but I’ve read enough of them (or am otherwise familiar enough with them) to make some recommendations based on what you may wish to learn more about, and at what depth you wish to learn. I can also give you some fair warning about some of their authors and how their own views shape their work.

Charles Sellers’ and Eugene McCormac’s biographies are the two oldest “true” Polk biographies today. McCormac’s is the very first, written immediately after Polk’s Presidential diaries were first published, and Seller’s was written a few decades later. These biographies are the most in-depth (each spans multiple volumes), however McCormac’s only includes information from Polk’s diaries as the correspondence was not yet published. Sellers benefits from some of Polk’s correspondence, but not all. Obviously that isn’t going to deter the average reader, but this section is about distinguishing each book so yeah.

Seigenthaler’s biography is essentially a pocket guide to Polk (it was commissioned as part of a larger series of short Presidential biographies), covering his life in about as much detail as I have here. Reading it probably won’t give you any additional information, but it is a good piece. I guess you could tell people you read that book to learn about Polk if you didn’t want to tell them you were reading a racist guy’s hour-long Substack article.

Walter Borneman’s biography is my personal recommendation for people today. As you can tell looking at the footnotes, it’s where I pulled most of the quotes used in this post. However, it doesn’t go in to as much detail as McCormac or Sellers, but it is one of the most recently published biographies, so it has the most up to date information (Polk’s correspondence was not completely published until just a few years ago). Often times you will see Borneman reference both Sellers’ and McCormanc’s biographies, which goes to show how influential they were. Generally speaking, this is probably the best bang for your buck as far as time goes, as it is sufficiently detailed without sacrificing some of the depth that Seigenthaler’s lacks.

Robert W. Merry’s biography was published only a couple years after Borneman’s and, as far as I’m aware, is the most recent Polk biography. I have only skimmed this one (plan on reading it soon), but holding both books here I can tell that Merry’s is a good bit thicker. If I had to guess, this book would be for those who want a little more detail than Borneman, but not multi-volume biographies like Sellers or McCormac.

William Dusinberre’s biography has a very obvious libtard tilt. The thesis of the book is basically that Polk is super evil because he had slaves and also didn’t address slavery in his Presidency, or during his time as Speaker of the House (when the Gag Rule was in place). It kind of sucks and is also not that compelling, because Polk did not own that many slaves compared to several other Presidents, and he was entirely neutral on the issue of slavery as President. He probably knew that his territorial expansion was going to cause issues with the slave debate, but he also knew that this was an issue for Congress to fight over and not him. Polk also wasn’t a cruel master by any accounts (most of his slaves were at a plantation far from him), and some accounts even say he was a very benevolent master to the slaves he had dealings with. Dusinberre is really just grasping at straws here I think, but his book has nevertheless come to dominate Polk discussions in the modern day simply because slavery is like evil or something (not true btw).

Amy Greenberg is another libtard biographer, but she has two books in the list. The first book is a biography of Polk’s wife Sarah, which is decent. Obviously you have to look past the feminist glazing, but Sarah really was a very incredible woman who was a better First Lady for Polk than probably anyone else could ever hope to be. Her social prowess made up for Polk’s general aversion to socialization and then some, and here intelligence undoubtedly made her an asset to Polk’s daily affairs outside of this. Her other book is titled: A Wicked War: Polk, Clay, Lincoln and the 1846 U.S. Invasion of Mexico so you can already tell where that’s going. This is, of course, the other criticism of Polk today: that he was mean to latinx o algo and that’s like… bad o algo. Refer to my previous section about why the beginning of the Mexican-American War was not that big of a deal.

As for the rest of the books, I haven’t read them and I’m not familiar enough with them to give a recommendation one way or the other. I imagine most of them are probably pretty alright though, but there’s a reason that Borneman, Sellers, and McCormac are the most referenced Polk biographies today.

>Polk was infertile and married Sarah Childless (pronounced in a funny Japanese way)

>James Pork was defeated by Lean Jimmy

>Baron von Rawback said Polk branded his slaves

Is early America a thinly disguised comedy?

Lol at Lincoln being cringe. US Grant also opposed the war but also wanted to genocide the Indians so at least half cool compared to Lincoln. I love his final quote and agree there should be biopic about him, as well as Washington, Jackson, Hoover, Eisenhower, and Nixon; but if made today they would sadly be cringe.

I absolutely love reading about American history! Greatest country ever!