I’m not here to beat the dead horse that is making fun of pseudointellectuals who think that repeating the names of fallacies like a broken record is some sort of ultimate defeater. We’ve all seen people do it, and it’s pretty clear that it’s stupid. It’s not even an actual argument most of the time, nor are the fallacies even applied correctly.

Regardless, I want to clarify a few things about a few specific fallacies and then throw my own into the ring.

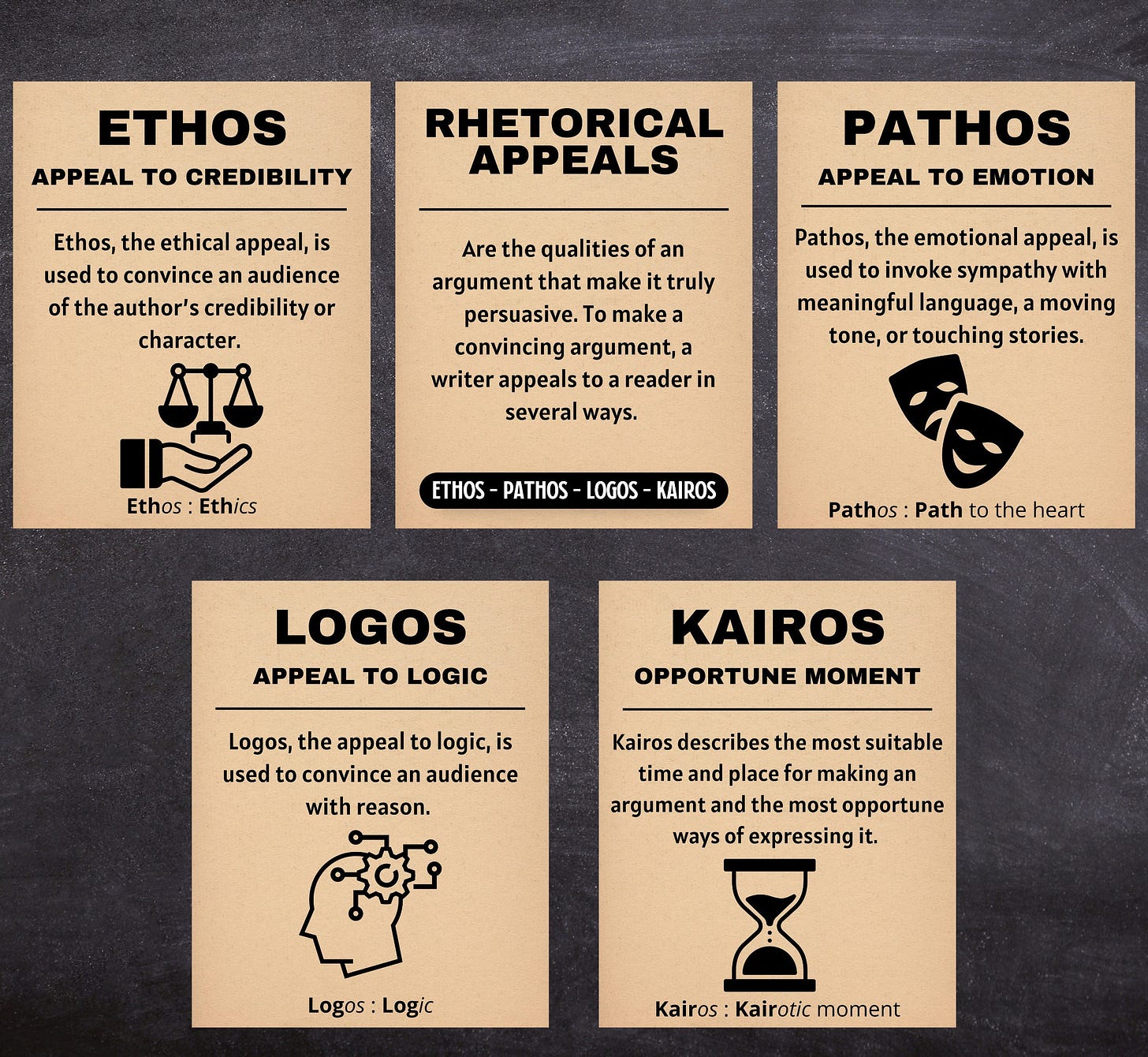

You all have probably seen this graphic before. I once repubbed it long ago (before I was Polk) when I was in high school. Most of these applications are either outright wrong, or leave at important information as to why they are fallacious. Firstly, these are all informal fallacies, meaning they relate to the content of the argument rather than the structure of the argument (formal fallacies relate to structure). This is an important distinction, because formal fallacies are much more obviously fallacious. I’ll provide an example to demonstrate this:

Premise 1: Bruce Wayne is Batman.

P2: Batman saved Gotham City.

P3: The citizens of Gotham City know that Batman saved Gotham City.

Conclusion: The citizens of Gotham City know that Bruce Wayne saved Gotham City.

This is a formal fallacy because there is no premise which alleges that people know Bruce Wayne is Batman. To rectify the fallacy, there would need to be a premise inserted between P1 and P2 that states something to the effect of “The citizens of Gotham City know that Bruce Wayne is Batman” (which would be a false premise, making the conclusion false anyways).

Informal fallacies, like those in the graphic above, do not work in the same way. Generally, they are divided into two subgroups: fallacies of relevance and fallacies of ambiguity. A fallacy of relevance occurs when someone brings up irrelevant information. A fallacy of ambiguity occurs when someone uses ambiguous language to obfuscate their point and often change during the discussion.

Fallacies of ambiguity are basically like when some moron refuses to take a concrete stance on something and just goes with the wind on things (think enlightened centrist), or when a conman dresses his language in a pleasing way to make otherwise repulsive statements more palatable. They, like formal fallacies, are pretty easy to identify if you have more than a room temp IQ, so I won’t focus on them here.

Fallacies of relevance are the most commonly used by pozzed Redditoids and their ilk. Things like Red Herring, Slippery Slope, Genetic Fallacy, Ad Populum, Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc, and Ad Hominem are all fallacies of relevance (that’s 6 out of the 12 in the graphic, though most of the remaining 6 can also be formulated as fallacies of relevance over fallacies of ambiguity). I want to address these 6 specifically, because they are the most commonly used by redditoids.

Ad Hominem

Starting with the most common. Ad Hominem is usually invoked by stupid people once you call them stupid, after which point they will declare themselves the victor in the debate and say that you were unable to refute their [supposedly] ironclad arguments, and so you resorted to petty name calling. What actually happened is that you refuted their claims (several times over, in fact) but they were too stupid to realize this, so you decided to take the gloves off. But, by calling this stupid person a moron, you did not actually commit a fallacy. I want to direct you to the example used in the original graphic above, the part where the robot says “I conclude you should not be debating while malfunctioning” and the other screams “Ad Hominem”. This is not a fallacy, because it is not irrelevant. The robot was malfunctioning, and malfunctioning does indicate impaired faculties, meaning you are not well-suited to intellectual endeavors. Similarly, if someone is stupid, calling them stupid is not fallacious because being stupid is relevant in intellectual discourse. What it is, is an examination of their character (Ethos).

A more poignant example of this (which I myself used on a professor before) is as follows:

(Political Science) Professor: “As Sigmund Freud once said: “‘…’”

Me: “Sigmund Freud was a gross pervert.” [This was just shy of a year after my original Freud Post btw].

P: “That’s a logical fallacy, Ad Hominem.”

M: “Actually, it isn’t fallacious. It’s an analysis of his Ethos, which is relevant to the discussion of his merits as a philosopher and psychiatrist.”

Hated that professor btw. Horribly disorganized, edgy atheist a la God’s Not Dead who defended his anti-theist remarks by saying he was married to a muzzie [paraphrased], and he had a poster of Che Guevara hanging in his office. When Trump was indicted, we spent almost the entire class listening to him ramble on about how orange man bad, despite it being a Modern Political Science class, where the most recently alive person was John Stuart Mill, who died in 1873. I frequently clashed with him on a number of topics, to a similar effect as described above. Despite this he incessantly asked me to take his Classical Political Science class the next semester. I politely declined.

Ad Populum

Ad Populum is basically the Pathos version of Ad Hominem (Ethos). You have to prove that an emotional appeal is irrelevant. The Ben Shapiro crowd loves to throw this one around (“Facts don’t care about your feelings”) but the simple fact of the matter is that this isn’t true. If anything, feelings don’t care about your facts (nothing inherently wrong with this btw, although there easily can be). The reality, however, is that you need a balance between logos and pathos (Ethos is frankly just a mix of the two, and Kairos is functionally the same as Ethos).

That is to say, removing feelings from facts is just as bad as removing facts from feelings. If you remove feelings from facts you end up with abominations like test tube babies raised by the state (shoutout Vic [iFunny] for believing this is a positive good btw). You need to articulate why feelings are best put to the side in a given debate, which is much easier said than done (contrary to what many people want to believe).

Red Herring

The Red Herring illustrates a more general gripe I have with discourse. Assuming that the Red Herring is itself on-topic and not wildly irrelevant, it still tends to represent an anecdote rather than a general trend. I really don’t have a problem with anecdotes, not like most people do anyway. I think most anecdotes provide invaluable information. Now, that’s not to say that I believe all black people are wholesome because I know a few black guys who aren’t violent criminals; they still commit a disproportionate amount of crime after all. The value of the anecdote, in my opinion, is that it often points to a general trend.

It’s the same logic behind the idea that stereotypes exist for a reason. Yes, there might not be an empirical study behind a stereotype/anecdote, but that doesn’t make it untrue. It just means there needs to be more thought put into the matter. Regardless, you should know not to bring up anecdotes and the like around libs, on account of their ornery nature.

Genetic Fallacy

The Genetic Fallacy is less commonly seen, and less commonly misapplied. Regardless, people generally don’t understand what actually makes it a fallacy. Frankly, you can judge things by their origins. If I buy a GPU from Wish.com, it stands to reason that what I get will not be a functioning GPU. Once again, you have to prove why the origins of whatever you’re talking about are irrelevant.

This is usually exceptionally hard to do, however. Often times, any attempt at proving why the origins of something don’t matter lead you to beg the question. For example, the Genetic Fallacy most often appears in religious debates. Specifically, atheists will suppose that religion(s) arise from tribal superstitions based around natural phenomena (like Zeus causing lightning or something) or the fear of death leading to the theistic promise of eternal life (most commonly used against Abrahamic faiths). The theist then invokes the Genetic Fallacy, but the atheist doesn’t understand what it fallacious about what he said, because his arguments were logically valid and he may have even had some scientific study to back it up. The problem, however, is that he is begging the question. In a debate about the existence of God, you can’t just assume that God does not exist any more than you can assume that God does exist. Agnosticism is the proper initial stance in such a debate, but by claiming that religions arose from tribal superstitions or something like that, you’ve already assumed that all religions are wrong. Thus, the atheist begged the question.

Conversely, if one were to say that Scientology was probably untrue, based on prior statements by the founder (about making a religion for personal gain) then that would be a proper argument. The details therein are relevant to the argument at hand, and you aren’t assuming details since we have direct evidence for these quotes, unlike religions that are thousands of years old.

Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc

Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc is in the same category as the “correlation does not equal causation” crowd. Sure, it’s not enough to just say that a preceding event caused a subsequent event, but that isn’t how most people argue anyways. I mean, if you get kicked out of 109 different countries spread across the entire globe, it’s probably you’re fault after all….

Also, just on a general level, correlation usually does end up with at least some degree of causation. Think of it like a reverse butterfly effect; sometimes seemingly insignificant things can have unanticipated consequences. If you genuinely can’t find some sort of causal link then that’s one thing, but most people just invoke Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc to avoid unsavory ideas like race realism or something, without ever engaging with the argument.

Slippery Slope

Slippery slope is just the inverse of Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc. Usually that slope is, in fact, very slippery. As you all know, they didn’t just want to be able to get married after all (they didn’t even want to get married, frankly). Just like Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc, Slippery Slope is usually invoked to avoid unsavory ideas. Several decades ago it was about how Hart-Cellar wouldn’t upset the racial demographics of America. A few years ago it was about how letting homos get married wouldn’t lead to anything other than them getting married. You get the point.

Fallacy of Validity

This one is a Polk(™) original (as far as I’m aware). I suppose it’s more of an informal fallacy, and it’s invoked when one supposes that because an argument is logically valid, then it must be true regardless of the truth of its premises. Think of it as someone who believes something “because it just makes sense”. Often, this belief is colored by a belief in a greater ideology and is typically reinforced by circular reasoning (in fact, I would consider this a sub-fallacy of circular reasoning) or something like that. For example, a formal argument that would be fallacious in this way is as follows:

Premise 1: The Catholic Church has a history of being “anti-science” and generally regressive.

P2: Being “anti-science” and regressive is undesirable.

P3: Undesirable things should be abolished.

Conclusion: The Catholic Church should be abolished.

You will see some form of this kind of argument from Redditors and the like. This argument is logically valid; that is to say each premise properly lends itself to the conclusion. However, the first premise isn’t true. The Catholic Church founded many universities in Europe, preserved a great deal of knowledge (certainly more than they ever destroyed), and served as the patrons for most of Europe’s greatest thinkers (including Galileo Galilei’s principle work on Heliocentrism, much to the Redditoid’s disbelief). But, because the argument “makes sense” (and supports their ideology) they agree with it.

This is, unsurprisingly, most commonly seen in cases of extreme liberal pedagoguery. The case above is an excellent example, but other cases exist as well.

In summation: give dorks swirlies.

Reckless and incompetent expounders of Holy Scripture bring untold trouble and sorrow on their wiser brethren when they are caught in one of their mischievous false opinions and are taken to task by those who are not bound by the authority of our sacred books. For then, to defend their utterly foolish and obviously untrue statements, they will try to call upon Holy Scripture for proof and even recite from memory many passages which they think support their position, although “they understand neither what they say nor the things about which they make assertion [1 Timothy 1.7].”

-Saint Augustine (De genesi ad litteram imperfectus liber, Book 1 Chapter 19 Paragraph 39)