A lot of the internet right, or really just the right in general be it Neocon or NeoFash, has a wildly inaccurate misunderstanding of what the Enlightenment actually was. This, and conceptions about contemporary Liberals, have colored (tainted, really) perceptions of classical Liberals like Locke. Beyond even that, The Enlightenment was not an intrinsically “Liberal” period, nor was it the advent of secularism/atheism like many crusader larper types will often portray it as. I maintain that the Enlightenment was a generally positive movement, though of course there were a number of thinkers who were pretty longhoused (we will get to this later). It was also a very ideologically diverse movement which produced arguments and schools of thought employed by many today, from Monarchists to Fascists.

It’s also important to understand at least a few important terms as they were used almost universally by Enlightenment Thinkers to establish a common frame of reference. The definitions are pretty universal, but each Thinker had their own unique spin on their interpretations, which will be covered as necessary.

The State of Nature/Man- Most of the time The State of Nature is used, but the State of Man means the same thing. This is just the state which man exists in prior to entering into the “Social Contract” which essentially just means before they created a civilization.

The Social Contract- This is what man “signs” (not literally, at least most of the time) in order to enter into a proper civilization. Sometimes this means actually agreeing to a hierarchical structure with a Monarch or what have you, other times this may be a loose confederation of peoples or something. It’s important to note that conquering people and adding them to your empire isn’t the same thing. That comes later in the process, and will be discussed momentarily.

The People- Straightforward; it’s just the average person who has signed the Social Contract. The citizenry.

The Sovereign- Also straightforward; the head of state. Monarch, President, Dictator, etc. Sometimes this is not an individual but rather a ruling body like a Senate.

The Leviathan- Comprised of two parts: The Body Politic (The People) and The Head (The Sovereign). This is a proper state, and is the result of a Social Contract.

To put these terms into perspective, imagine a group of disparate men and their small, immediate, families. Each man exists in the State of Nature where their only concern is the wellbeing of themselves and their family. Eventually the decide they have had enough of fighting with each other and realize it would be more effective if they banded together. The men all agree to stop fighting one another for resources and decide to conduct a trial by combat to see who will lead their new tribe. The strongest man wins and becomes The Sovereign, the others become The People and together they are The Leviathan. The Leviathan proceeds to conquer nearby tribes and villages, growing in size and bringing more people into its Social Contract (not exactly consensually but Might Makes Right and all). Eventually, the Sovereign develops into a proper Monarch instead of a tribal chieftain, and the descendants of his original band of warriors become the Aristocracy. The exact mechanics of Leviathan change; from tribe to kingdom, etc. but overall it remains the same, and so the definitions apply equally.

What is “The Enlightenment”?

People have a wide range of perceptions as to the nature of The Enlightenment. This typically manifests either substantively (i.e.: what The Enlightenment was ideologically) or literally (i.e.: when it was, and thus who is an “Enlightenment Thinker”), and sometimes there is a degree of overlap between the two, particularly if their perception of Enlightenment ideology is colored by an anachronistic understanding of when the Enlightenment was.

Starting with the exact dating, as it is the simpler of the two, most historians generally agree that it began in the mid 17th century and ended at the beginning of the 19th century. Specifically, René Descartes' Discourse on the Method (1637) or Thomas Hobbes Leviathan: Or the Matter, Form, and Power of a Commonwealth Ecclesiastical and Civil (1651) are generally considered the beginning of the Enlightenment, and the death of Immanuel Kant in 1804 is considered the end. Generally, I tend to consider 1651 to be the beginning of The Enlightenment as Leviathan had a far greater impact on Enlightenment discourse than Discourse on the Method did (which I generally consider a precursor to the Enlightenment).

It’s quote difficult to understate the impact of Leviathan. Hobbes’ publishing of Leviathan was basically the Early Modern European Intellectual equivalent of asking if the Holocaust actually happened to a room half full of Jews and half full of skinheads and then locking the door. Leviathan instantly made Hobbes a demon to some and a prophet to others. Not only were the terms used/popularized by Hobbes in Leviathan mainstays of Enlightenment discourse for the rest of the era (it’s worth noting that the definitions given at the beginning are virtually all taken directly from Leviathan), but the debates of the Enlightenment themselves all basically boiled down to whether or not you had a Hobbesian view. Was the State of Nature something to be actively avoided at all costs, or was it the ideal state of Man? Were you a Monarchist or a Liberal? Are Natural Rights fake or are they actually God-given?

The Enlightenment is probably best described as a Reddit comment that says “I think poor people will kill each other and themselves unless the King beats them into submission” (Hobbes), with 3,000+ replies of 20 different dudes each writing dozens of comment text walls either crying about how wrong Hobbes is or saying how GOATed he is for saying that. Also Hobbes’ original comment has neutral karma somehow.

By contrast, Descartes was moreso the bridge that applied the rationale of the Scientific Method (namely: Empiricism as described by Sir Francis Bacon in his multi-part magnum opus: The Great Instauration). Obviously, philosophers had always been inclined to reason, but the way this manifested prior to the Enlightenment was substantially different. Part of this is due to the shift away from the Aristotelian Method (Deductive Logic) to the Baconian Method (Inductive Logic). The effect is quite obvious in The Enlightenment: every single proposition made by authors is immediately followed by either a historical example in support of it, or an everyday application that is easily verifiable. Basically, this was the beginning of “Source?” in academic discourse; if you couldn’t cite the Bible, a scientific fact, or an everyday observation to support your ideas then other Enlightenment Thinkers would rip you to shreds. Essentially, Descartes enabled The Enlightenment and Hobbes actually started it.

But that doesn’t really answer what The Enlightenment actually was, just when.

Most people view The Enlightenment as the genesis of Liberalism, and while this is to some extent true, there is much more to it than that. “Enlightenment Ideology” is not as monolithic as, say, Communist Ideology or Fascist Ideology. To be a Communist or Fascist you have to adhere to at least a few basic principles, even though Communist/Fascist states can look quite a bit different from one another (i.e.: The USSR vs. Maoist China). Conversely, “Enlightenment Ideology” is something of a paradox. The Enlightenment was not composed of heterogenous ideals, and was instead a period of fierce debate between highly contrasted worldviews.

Take, for example, Thomas Hobbes and his book Leviathan as mentioned earlier. Hobbes himself was a staunch Monarchist with the entire premise of Leviathan essentially boiling down to these three concepts:

The State of Nature is chaotic and evil and any sane human seeks to avoid it at all costs.

The only way to avoid the State of Nature is by forming a Social Contract to agree to not kill each other.

Monarchies are the best form of Social Contract as they are the most stable.

Hobbes was, however, a Monarchist who believed that Kings derive their authority from the Social Contract (essentially consent of the governed, but once you “sign” the contract you cannot revoke your consent). On the other hand, many other Enlightenment Monarchists dug their heels in and stuck with the Divine Right of Kings. Probably most famously among these was Robert Filmer, and his Patriarcha, or The Natural Power of Kings (worth noting that it wasn’t published until 1680, 27 years after Filmer’s death and likely about 40 years since it was actually completed. Regardless, it is generally considered an “Enlightenment work” due to it’s significant role in contemporary discourse.) which still has an influence on modern Tories today (especially High Tories). Naturally, Divine Right Monarchists did not get along with Social Contract Monarchists, and Filmer critiques Hobbes’ work just as much as he does the work of Republicans and other more Liberal types.

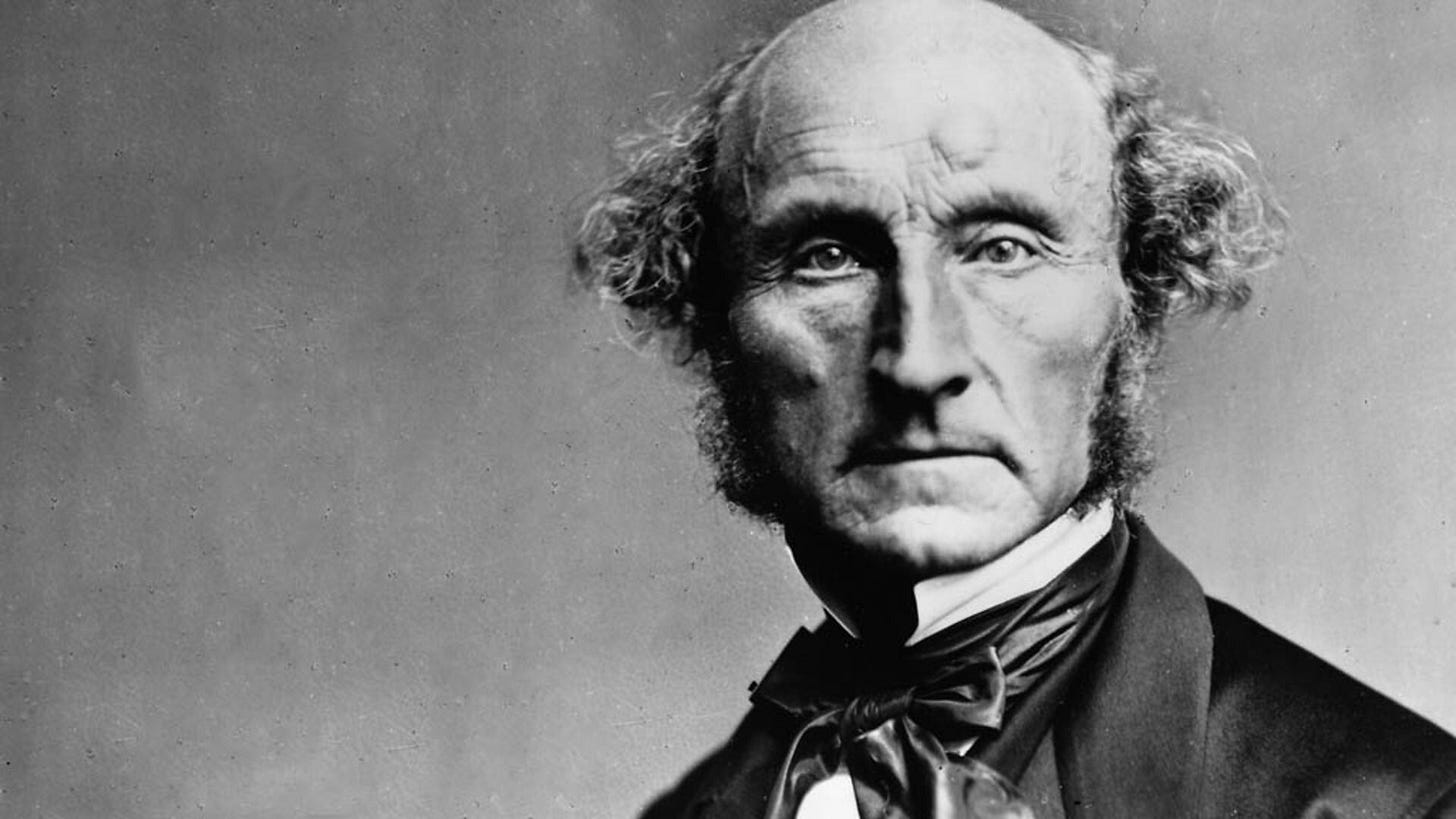

Similarly, the more Liberal types were also not exactly in ideological lock-step. John Locke, the archetypal “classical Liberal”, spends the entire first half of his famous Two Treatises of Government critiquing Robert Filmer and his supporters, and in the second half he lays the foundation for modern Libertarian political theory.

Though the earth, and all inferior creatures, be common to all men, yet every man has a property in his own person : this no body has any right to but himself. The labour of his body, and the work of his hands, we may say, are properly his. Whatsoever then he removes out of the state that nature hath provided, and left it in, he hath mixed his labour with, and joined to it something that is his own, and thereby makes it his property. It being by him removed from the common state nature hath placed it in, it hath by this labour something annexed to it, that excludes the common right of other men : for this labour being the unquestionable property of the labourer, no man but he can have a right to what that is once joined to, at least where there is enough, and as good, left in common for , others.1

For Locke, private property is essential to liberty. This is also where we begin to really see the idea of “God-given rights” as Locke believes that man has a right to property as per Genesis where God gives Adam dominion over Earth. This is, of course, contrasted with Filmer’s view where God ALSO gave Adam dominion over the Earth, but to Filmer this dominion was given as a monarch, whereas Locke insists the Earth was given to all men in kind.

Thus we have examined our author's argument for Adams monarchy, founded on the blessing pronounced, Gen. i. 28. wherein I think it is impossible for any sober reader, to find any other but the setting of mankind above the other kinds of creatures, in this habitable earth of ours. It is nothing but the giving lo man, the whole species of man, as the chief inhabitant, who is the image of his maker, the dominion over the other creatures. This lies so obvious in the plain words, that any one, but our author, would have thought it necessary to have shewn, how these words, that seemed to say quite the contrary, gave Adam monarchial absolute power over other men, or the sole property in all the creatures ; and methinks in a business of this moment, and that whereon he builds all that follows, he should have done something* more than barely cite words, which apparently make against him ; for I confess, I cannot see any thing in them, tending to Adams monarchy, or private dominion, but quite the contrary. And I the less deplore the dulness of my apprehension herein, since I find the apostle seems to have as little notion of any such private dominion of Adam as 1, when he says, God gives ns all things richly to enjoy, which he could not do, if it were all given away already, to monarch Adam, and the monarchs his heirs and successors. To conclude, this text is so far from proving Adam sole proprietor, that, on the contrary, it is a confirmation of the original community of all things amongst the sons of men, which appearing from this donation of God, as well as other places of scripture, the sovereignty of Adam, built upon his private dominion, must fall, not having any foundation to support it.2

And yet, this framework was not accepted by all either. Just as Robert Filmer positioned himself against Thomas Hobbes, and Locke against Filmer, Jean-Jacques Rousseau would himself take a stance against Locke. Whereas Locke believed that the right to property was the fundamental right of humans, Rousseau believed that property was the source of all inequality:

The first person who, having fenced off a plot of ground, took it into his head to say this is mine and found people simple enough to believe him, was the true founder of civil society. What crimes, wars, murders, what miseries and horrors would the human Race have been spared by someone who, uprooting the stakes or filling in the ditch, had shouted to his fellows: Beware of listening to this impostor; you are lost if you forget that the fruits belong to all and the Earth to no one! But it is very likely that by then things had already come to the point where they could no longer remain as they were.3

As a slight tangent, it is really no wonder the French Revolution turned out the way it did. Rousseau, being probably the single most impactful philosopher behind the theory of the French Revolution, was quite clearly a proto-Marxist. Rousseau also had wildly different views on the State of Nature than almost all of his contemporaries, wherein they viewed the State of Nature as chaotic and anarchical while Rousseau saw it as comparable to the Garden of Eden where no individual claimed anything for their own and each man took freely from the Earth “from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs.” Once again, betraying a very proto-Marxist outlook on the world.

I could go on and on presenting excerpts from various Enlightenment Thinkers and how their ideas wildly contradict one another in order to disprove the notion that the Enlightenment is nothing more than the genesis of Liberalism, or even the more basic assumption that “Enlightenment Ideology” is actually a thing, rather than a self-contradiction. I think you get the point, however. Instead, as I’ve shown, these Enlightenment Thinkers were very much at odds with each other and, more to the point, the Enlightenment is only the source of Liberalism insofar as it is the source of all modern political stances of note.

To lay it out more clearly:

Thomas Hobbes- Laid the groundwork for dictatorial/totalitarian/statist philosophies like Fascism, essentially shifting the right to govern from the Divine Right of Kings to the more explicitly nationalistic Social Contract wherein The People have a mutual obligation with The Sovereign, together forming The Leviathan.

Robert Filmer- Defends the traditional position of the Divine Right of Kings, thus maintaining the conservative approach to Monarchy.

John Locke- Establishes the foundation of Libertarianism, proposing Free Market ideals of Capitalism and individual rights to property.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau- Lays the groundwork for Marxism by outlining a utopian society where individual property is seen as barbaric and the root of all evil.

Not exactly one coherent and unified “Enlightenment Ideology” nor is it entirely Liberal in nature.

It’s also worth mentioning that I am not going to delve into each and every Enlightenment Thinker’s political philosophy here. That would make this post 100x as long as it already is and wouldn’t really add anything to the discussion. Instead I’m mainly going to limit myself to an analysis of the above four Thinkers, as they are arguably the most influential and general reflect the primary schools of thought during The Benightment, and so make a good litmus test for other Thinkers.

What The Enlightenment is Not

Liberal

The previous section defined The Enlightenment as a period starting with the publication of Hobbes’ Leviathan and concluding with the death of Kant, which was made distinct not by ideological homogeneity but by a diverse array of highly conflicting political ideologies. This implicitly precludes The Enlightenment from being “Liberal” in any meaningful sense, and I was quick to point that out. However, there is more to discuss in that regard.

As mentioned in the above section, The Enlightenment was the genesis of Liberalism insofar as it was the genesis of all major political orientations of the modern day. One could therefore argue that The Enlightenment could still be considered the cause of Liberalism in that it is ultimately responsible for Liberalism’s popularity. I think you you still be hard-pressed to actual demonstrate that, however.

As many others have pointed out, “Liberal” in The Enlightenment sense of the word is not at all similar to the modern term. That is why, general, Enlightenment Liberals are referred to as “Classical Liberals” and are said to have more in common with modern Libertarians than modern Liberals. I think, however, most people understand this by now.

If any element of the Enlightenment era is responsible for the promulgation of Liberal ideology, it would be the French Revolution. Even then, the French Revolution is more a result of Rousseau’s brand of political extremism than it is any other single Enlightenment Thinker. Of course, Monarchists of any flavor were opposed to the French Revolution entirely, and Classical Liberals (most famously Thomas Jefferson) did often express at least some support for the Revolution. I think, however, it’s sort of unfair to blame these Classical Liberals for their lack of foresight. At the time, the French Revolution seemed like a just cause to them, and they had no real reason to realize how bad things would be. And in fact, many of them did come to view the French Revolution as a bad thing, and virtually all of their successors did as well.

We will talk more about what actually was the progenitor of modern Liberalism a bit later, however.

Atheist

TradCaths and OrthoBros especially like to bemoan The Enlightenment as the birth of atheism. Generally they describe The Enlightenment as a secular attempt to create morality/political structures without God, heightening Science/Reason over Religion, etc. Generally when they say this, they just betray the fact that they have no idea how to read.

All of the Enlightenment Thinkers were religious, with a mix of Catholics, Protestants, and deists. Some claim that the heightened popularity of deist thinkers and the subsequent influx of deists themselves is to blame for the increase in atheism. In general I think it is really a reflection of TradCaths/OrthoBros hating to see a Protestant Wigga going hard in the paint, but whatever.

Looking, again, at Thomas Hobbes as an example (Hobbes was himself a Deist) we start to see the TradCath/OrthoBro interpretation of a “grossly secular” Enlightenment fall apart. Most obviously is the fact that the last two parts of Hobbes’ four part Leviathan are titled “Of A Christian Common-Wealth”4 and “Of The Kingdome of Darknesse”5 respectively. In the former, Hobbes places God as “Ultimate Sovereign” and the true king of any rightly society, and in the former Hobbes lays out his disdain for pagan religions, Satan, etc. Of course this is all colored by his Deist perspective, namely that he believed things like literal angels and demons were fanciful (and even argued they were relics from pagan times), but it still demonstrates his explicit desire for a Christian society, to the point where he believes they are the only societies which can prosper.

Robert Filmer was quite obviously a Christian (obviously as an English Divine Right of Kings advocate he was an Anglican) so there isn’t much else to discuss there. I suppose it’s worth noting that he believed that all kings were literal descendants of Adam, who was the first Monarch as anointed by God. This is John Locke’s principle issue with Filmer and what Locke spends most of his time attacking in the First Treatise, mainly because such a claim would be impossible to prove and is almost certainly false. Filmer had other ideas too but they tend to get overshadowed by his peculiar beliefs regarding Adam, mainly due to Locke’s response. That being said, modern historians have taken to looking back at Filmer on his own merits, and pointed out that he had many interesting ideas. Anyway that is sort of a side tangent.

Turning to John Locke, he has some very interesting things to say. Specifically, in his A Letter Concerning Toleration he absolutely dogs on atheists in probably the funniest ways imaginable.

Yet were those kings and queens of such different minds in point of religion, and enjoined thereupon such different things, that no man in his wits (I had almost said none but an atheist) will presume to say that any sincere and upright worshipper of God could, with a safe conscious, obey their several decrees.6

Lastly, those are not at all to be tolerated who deny the being of a God. Promises, covenants, and oaths, which are the bonds of human society, can have no hold upon an atheist.7

It’s important to note that Locke did have unusual beliefs regarding Christianity. Locke was raised Calvinist, however he later adopted a Socinian stance, though some historians argue he may have shifted towards Arianism later in life as some of his views began to diverge from the Socinian norm. Regardless, he still believed in the truth and necessity of Miracles mentioned in the Bible, and that this was also in accordance with human reason.8 And of course, as mentioned earlier, Locke frequently cites Bible verses to support his arguments, which are all ultimately predicated upon God giving Earth to Adam/mankind.

Lastly, Roussea had a rather turbulent religious life. He was raised Calvinist, but converted to Catholicism early in his life, only to go back to his native Calvinism as part of his “moral reform” which largely coincided with his Enlightenment work. At some point in his life, he began to express more deistic views, especially in regard to Original Sin which he believed to be false (not surprising since he glazes the State of Nature). I have seen some people claim that Rousseau was an atheist later in life but I’ve never seen any evidence to back this up nor have I ever seen a scholar claim this. I think it’s moreso a product of TradCaths (understandably) not liking Rousseau and conflating deism with atheism.

The True Origins of Liberalism

As

expertly put it:If anything, it’s [Liberalism] more like a chimera of Maoist anti-Imperialism and Western Marxism (maybe some Trotskyism?).9

Modern Liberalism is a chimeric beast of 20th century Marxism and 19th century post-Enlightenment discourse. Like it’s ideological predecessors, modern Liberalism seeks to “immanentize the eschaton”, and views this as the ultimate end goal.

The Utilitarian seeks to create a society where “harm” does no exist.

The Marxist seeks to create a society where inequality and hierarchy do not exist.

The Libtard seeks to create a society where Whypipo do not exist, as they are the root cause of harm, inequality, and hierarchy.

And so, to understand the origins of modern Liberalism, one must understand the root of ideas like “harm principle morality” and the various origins of equality movements. It’s worth noting that I have discussed Utilitarianism before in a related capacity, where I actually agreed with the overall conclusion drawn by Utilitarianism’s father Jeremy Bentham, insofar as:

Natural Law does not exist at all and Rights are instead agreed upon and enforced by the State.10

Similarly to Hobbes, Bentham and co. believed that God did not provide “Natural Rights” to man, but instead these rights were agreed upon in the Social Contract as one of its terms. But where Hobbes believed that God simply did not award man any rights, beyond the right to his own body, Bentham believed that God didn’t exist and therefore could not award rights to man.

In this regard, Bentham might be considered an “Enlightenment Thinker” as he published several works in the last two decades of the Enlightenment, mainly critiquing things like The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen and other pieces defending natural rights (including our Declaration of Independence). However, it’s sort of improper to consider him an Enlightenment Thinker as by this point of The Enlightenment, theory had largely given way to praxis. Hobbes had been dead for a century by the time Bentham (anonymously) published his first work, Locke had been dead for 70 years. Of the “big four” mentioned in the beginning of the article, Rousseau was the only one who was alive for Bentham’s first publications, but he died two years after Bentham’s earliest work.

By this point, “Enlightenment Thinker” meant people like the Founding Fathers or French revolutionaries who were implementing Enlightenment ideals into actual statecraft, and less on the actual theorycels like Hobbes and Locke. In that sense, Bentham can only really be considered an Enlightenment Thinker insofar as he was malding at the students of actual Enlightenment Thinkers for believing God was real. Seriously, Bentham was rabidly atheist and it was kind of funny.

Anyway, that’s why I generally do not consider Bentham an Enlightenment Thinker, which is an important point to clarify for the purposes of this article. The latter half of the Enlightenment was mainly about praxis and less about theory, and even aside from that Bentham only engaged in one-sided dialogues with Enlightenment Thinkers, and would not himself gather a serious following until the early decades of the 19th century.

The 19th century is really where the genesis of modern Liberalism takes place. Some historians call this the “post-Enlightenment period” but I call it the “Age of Frivolous And Gregarious Gay, Ostentatious, Thinkers” or the “Age of F.A.G.G.O.Ts” for short. This is where we see individuals like Jeremy Bentham, his successor John Stuart Mill, and Karl Marx himself begin to amass a following.

It is also the period in which radical social change began to be advocated for publicly. Because I want to limit myself to emphasizing the Utilitarian ancestry of Liberalism, I will limit myself to only providing examples from the works of Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill, the to most eminent Utilitarian thinkers.

Jeremy Bentham wrote the first known argument for homosexual law reform in England, authored around 1785 but unpublished until 1978 when the Journal of Homosexuality published it. In it, he argues that homosexuality does not weaken men, that it is not immoral, that punishing homosexuals are unjust, and the historically homosexuality was not uncommon.11

Jeremy Bentham invented the Panopticon.12

Jeremy Bentham is largely responsible for usury laws being repealed in the Western world.13 This was also a direct response and critique of Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations.

Jeremy Bentham was one of, if not the, first people to whine about Imperialism/Colonialism.14

John Stuart Mill was one of the first proponents of women’s rights, and probably the most influential of his era.15

John Stuart Mill was a staunch abolitionist.16

John Stuart Mill favored Socialism, especially in his later years, coming to sympathize with the utopian socialists of his day.17

I hope I don’t have to explain to you how each of the above points is nothing more than “wokeism” of the 19th century, and the foundation upon which modern wokeism rests.

In these ideals, we can see the evolution of a rampantly tolerant ideology seeking to elevate the lowest members of society to the side of peers. While both Bentham and Mill were race realists and sometimes even flirted with ideas of the inferiority of non-Whites such a stance was not exactly uncommon in the 19th century. It was simply a rational conclusion. And yet, despite this, they refuse to follow the logical conclusions one would draw from this.

What is more alarming, however, is the insidious desire for control which Bentham betrays in his scathing criticism of anti-usury laws and support for the panopticon.

All of this comes together to inspire and amplify Marx, and to arm the neo-liberals of the 20th century with rhetorical appeals against what is obviously the nature of reality.

It is difficult to imagine someone like Hobbes, Locke or Adam Smith coming to support these ideas. On some level, it is even difficult to imagine Rousseau himself coming to support Utilitarianism, if only because of the wildly contrasting views of Natural Rights. Thus, it becomes very difficult to maintain the position that The Enlightenment is properly understood as the source of modern libtardation, particularly in the face of an alternative in Utilitarianism which so eagerly grasps for that title.

Good essay, as per usual. I think empiricism was really cemented by Locke, rather than Descartes, in his series of debates over the matter with Leibniz. Descartes/Leibniz were pioneers of the scientific method but still accepted the power of reason and the existence of innate ideas. Yes, Locke was not an atheist, but his empiricist and nominalist beliefs would become fuel for Atheists centuries later. Hume was also a thinker who contributed to the "Atheist" reputation of the enlightenment. Obviously kind of dumb when Leibniz and Pascal's arguments are equally relevant in favor of theism today.

I wouldn't really consider Rousseau the precursor to Marx either. He was more of an anarchist.

I've waited patiently for this for so long!